Charlestown Crisis Refuge District by Kris Menos

Boston, Massachusetts (Harborpark District)

MIT Urban Design Studio

Professor Miho Mazereeuw

Envisioning an alternative history in which the U.S. moved significantly ideologically leftward in the 2016 election, this urban project proposed the development of a flexible and adaptive neighborhood for humans in search of refuge in the Harborpark District of Boston, along the north edge of the Charlestown Waterfront. As part of a larger reparative national project, this mixed-use modular residential zone would be publicly funded, developed, and operated (with significant community input and participation) to house humans coming from precarious conditions around the world. Regulations for additional development would allow for various forms of small-scale private and personal ownership to arise within the Refuge, giving inhabitants — no matter their country of origin — the opportunity to settle down and productively invest in the community. The primary concerns of this project would be efficiency of construction, ease of adaptability, abundance of amenity, and above all, meaningful habitation for the occupant.

FICTIONAL SCENARIO: Within the United States Federal Government, Democrats, Socialists, and Progressives control more than two-thirds (enough to vote down a filibuster) of the House of Representatives, Senate, and occupy the Presidency. The United States joins the International Coalition of Advocates for Refugees, a unified group of cooperating nations and organizations with the purpose of humanely and efficiently relocating refugees of global crisis, catastrophe, and instability.

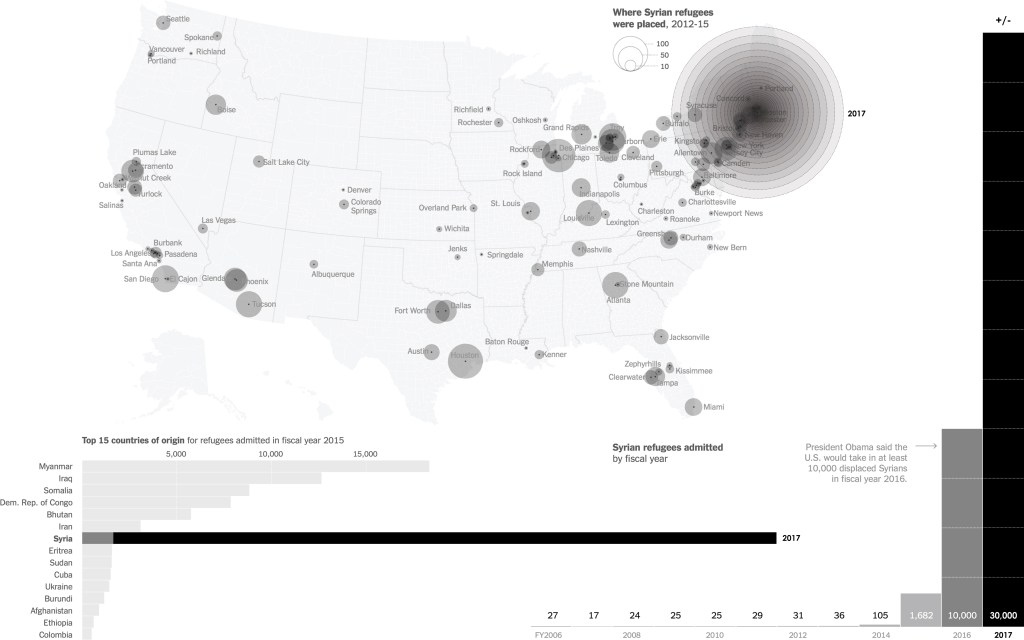

Projection [Incoming Humans; Base image via The New York Times]

Building on former President Obama’s 2015 declaration that the U.S. would accept 10,000 refugees of the crisis in Syria in 2016, in conjunction with immigration reform legislation, the U.S. Federal Government passes the 2017 International Refugee Liberty Act. The Act allocates funds for planning and implementing the mission of the International Coalition on U.S. soil. The progressive state of Massachusetts and the bay city of Boston volunteer to participate in launching the program, with a goal of accepting up to 30,000 humans in 2017.

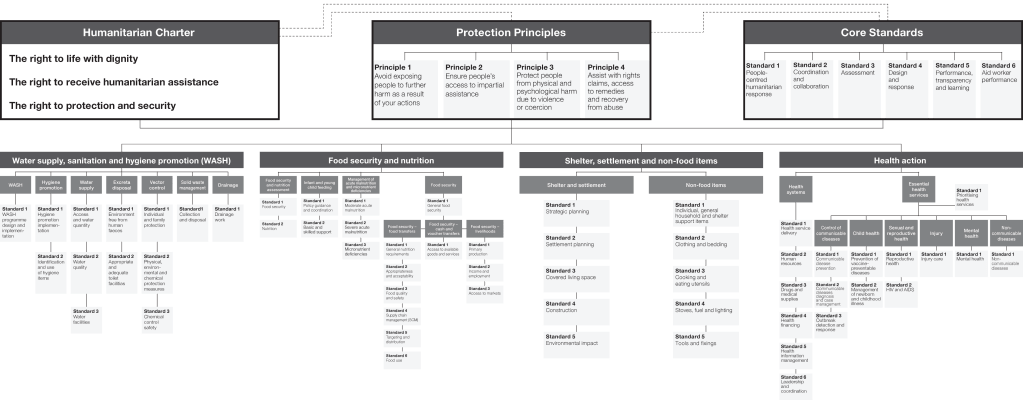

Charter [Diagrams compiled and rearranged, from The Sphere Project’s “Handbook” 2013 edition]

These local and state governments commit to the Sphere Project’s “Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response” to adopt a baseline of pre-established proven standards for the development.

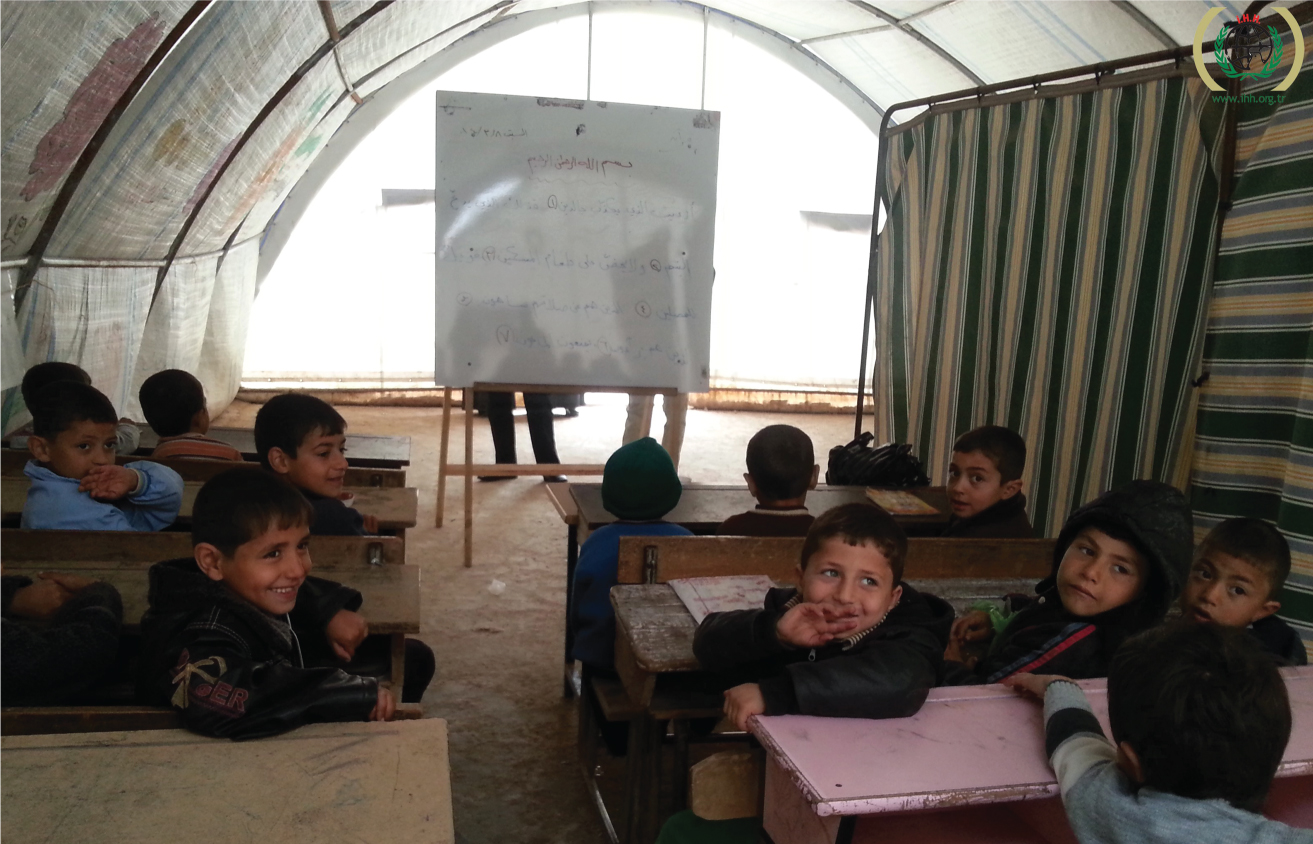

Alternatives [Babunnur and Babusselam Syrian refugee camps in Aleppo, via IHH Humanitarian Relief Fund]

This aids in the project’s mission to provide a more stable and durable alternative to existing sites of refuge, such as the Babunnur and Babusselam Syrian refugee camps in Aleppo.

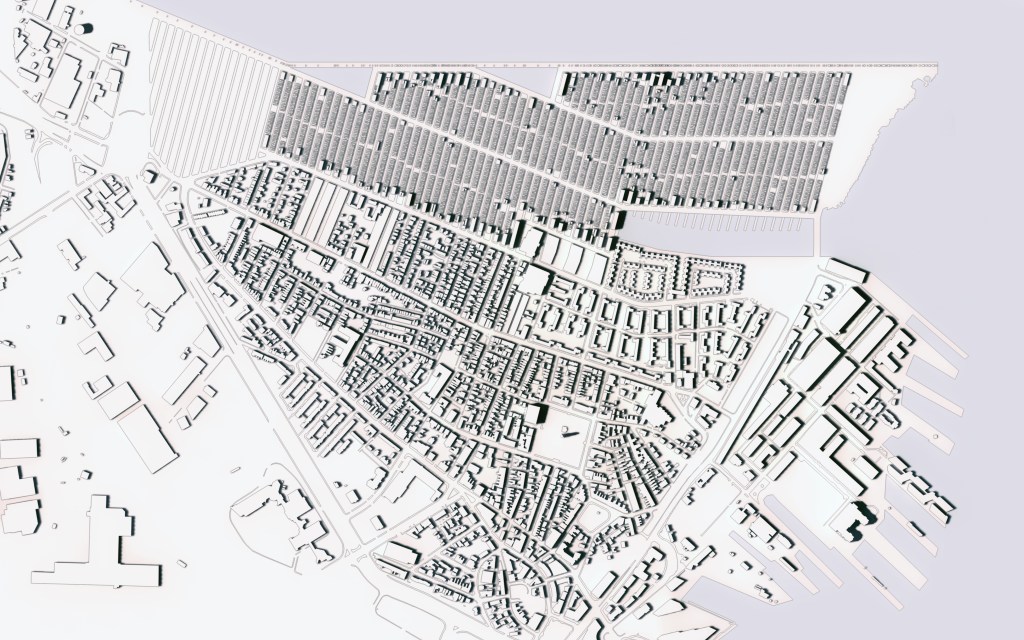

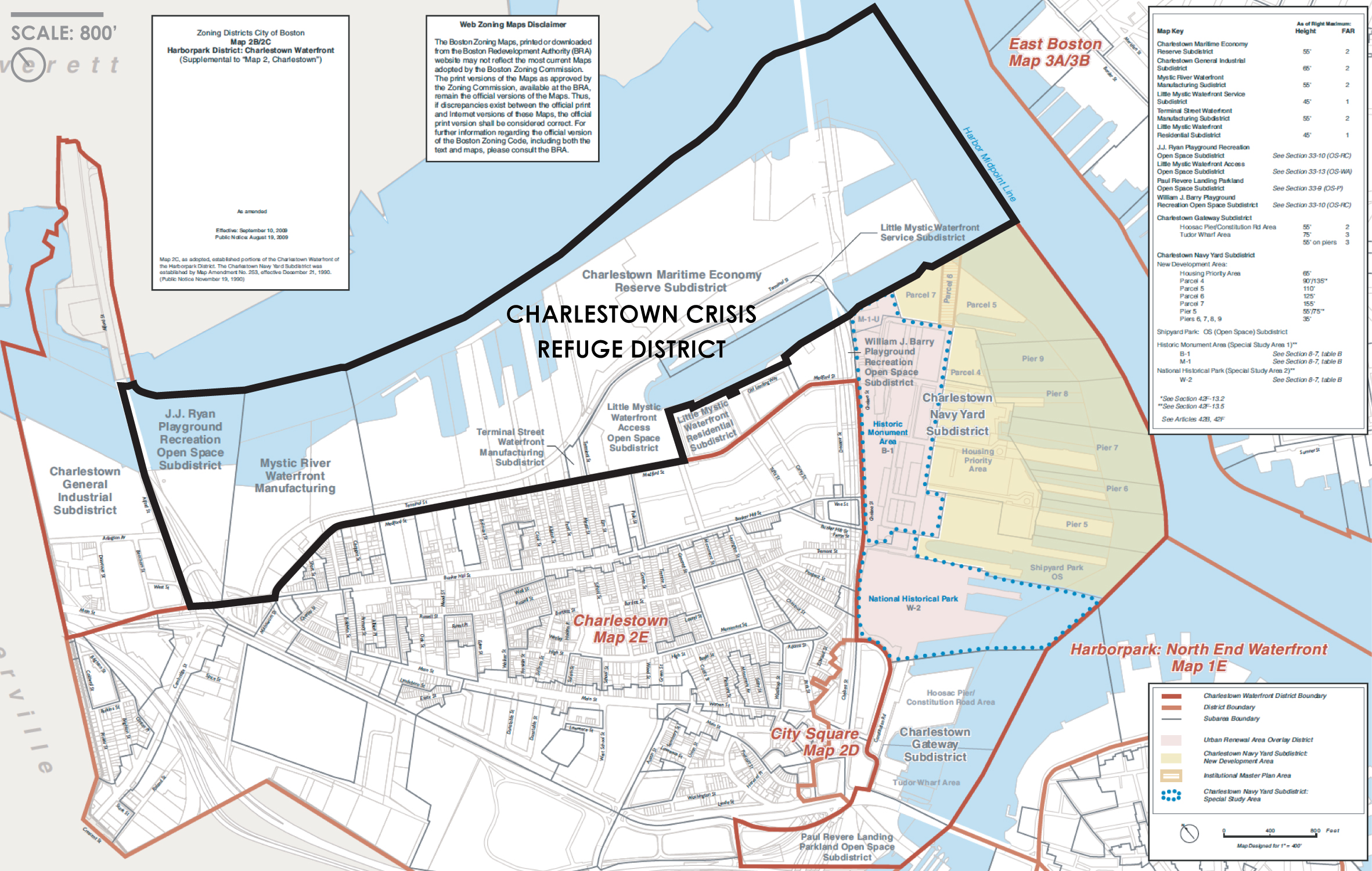

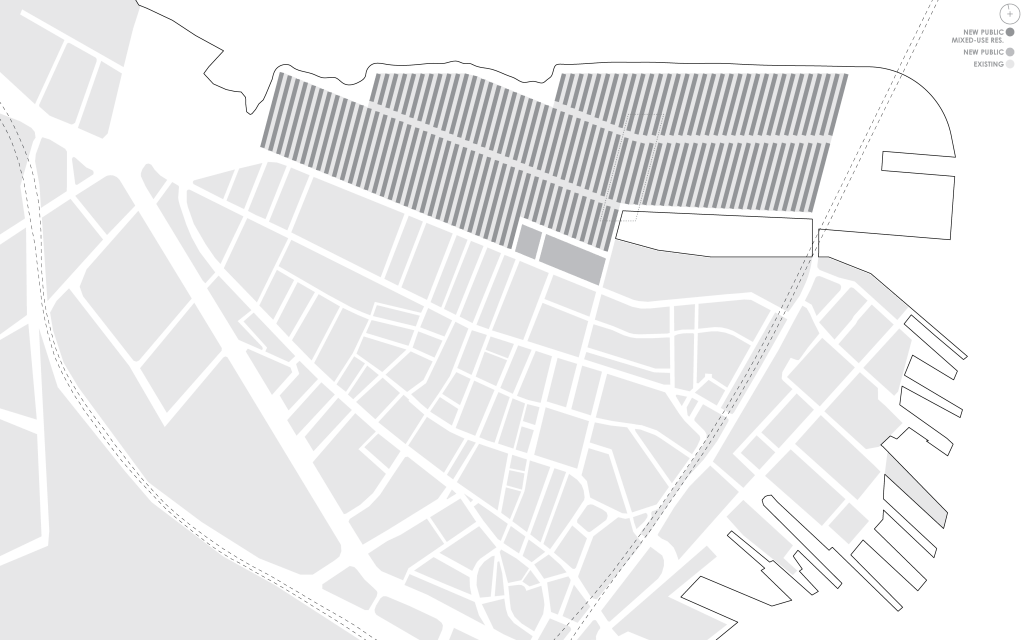

Harborpark District, Charlestown Waterfront: Zoning Map [Via Boston Development Authority] // Land-Use Analysis Map [Via City of Boston GIS Data, by Jie Bao]

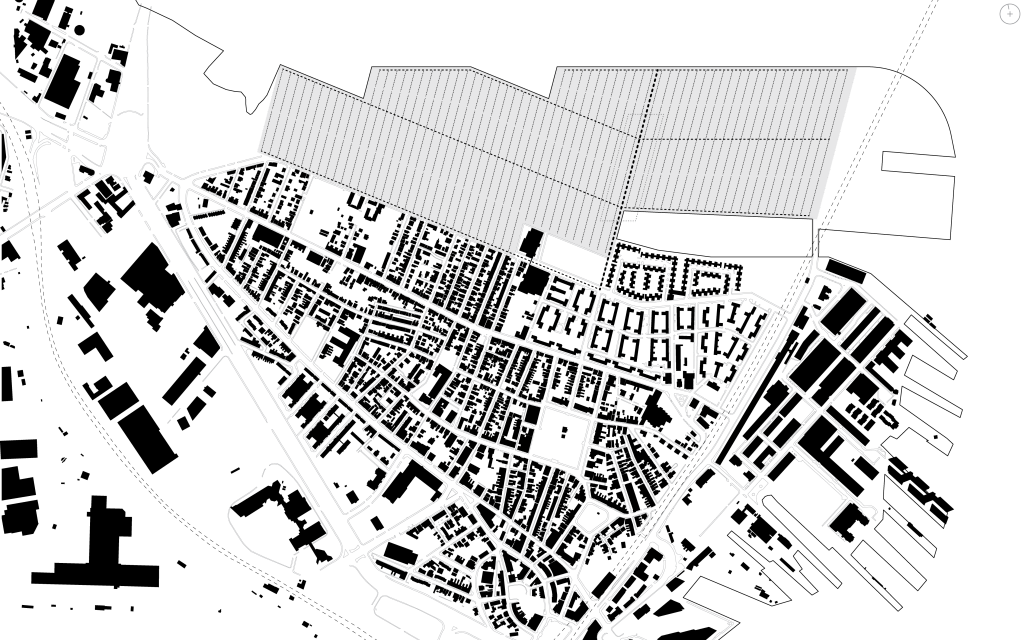

Using a combination of international, federal, state, and local funds, the city of Boston purchases the privately owned properties within the Charlestown Maritime Economy Reserve Subdistrict and some of the smaller adjacent Subdistricts. The city rezones the site’s land use classification from a mix of “Transportation” and “Industrial” to “Public Service” (under Boston Property Type Classification Code 9) and renamed as the Charlestown Crisis Refuge District.

The Refuge District will receive and comfortably house incoming flows of humans for varying periods of occupancy, ranging from weeks to years. Some humans will choose to disperse further into the country, and some humans will choose to remain. The site will also serve as a base of operations for coordinating these dispersal efforts. The goal of the site will be to humanely and comfortably accommodate and service fluctuating levels of incoming human beings with diverse lifestyles and in varying levels of permanence. The District will be home to refuge-seekers, skilled professionals, educators, administrators, volunteers, and visiting scholars, both local and from abroad.

Aerial Drone Photo [Existing site, Mystic River, and town of Everett to the north, via Jamie Farrell]

The existing site is predominantly occupied by a privately owned automobile import-export, storage, and distribution terminal, as well as a primary storage hub for the Boston Department of Transportation’s winter road salt supply.

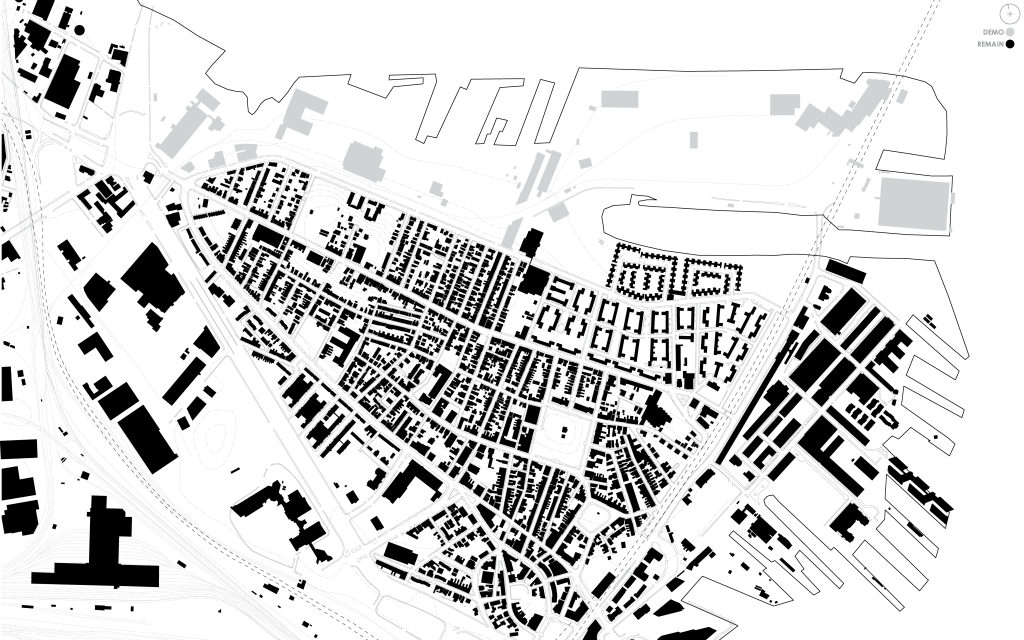

Site Plans: Existing [Charlestown Neighborhood, via City of Boston GIS Data]

The site and its surrounding locale has ample pre-existing transportation infrastructure to be used for accepting incoming human beings, for their comfortable habitation and ambulation, and for aiding in their voluntary dispersal:

- (A) Pedestrian access: ample sidewalk, covered areas

- (B) Bus access: frequent stops

- (C) Automobile access: two two-laned roads, Terminal Street headed west, Chelsea Street headed south

- (D) Railway access: stations south and west, terminal across the river to the north

- (E) Barge, ferry, and boat access: large dock, enough to fit two medium-sized cargo ships

- (F) Airplane access: Logan International Airport across the river to the east

In terms of car travel, rather than forcing inhabitants to rely on procuring, storing, and maintaining private vehicles, the state establishes a publicly operated rideshare service, to be autonomously run when the technology allows.

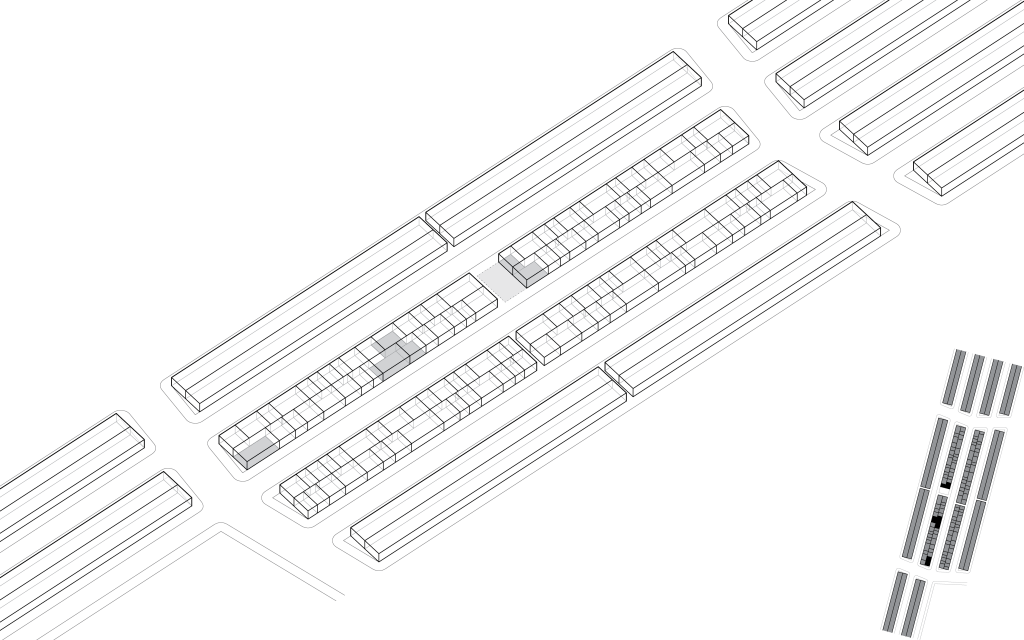

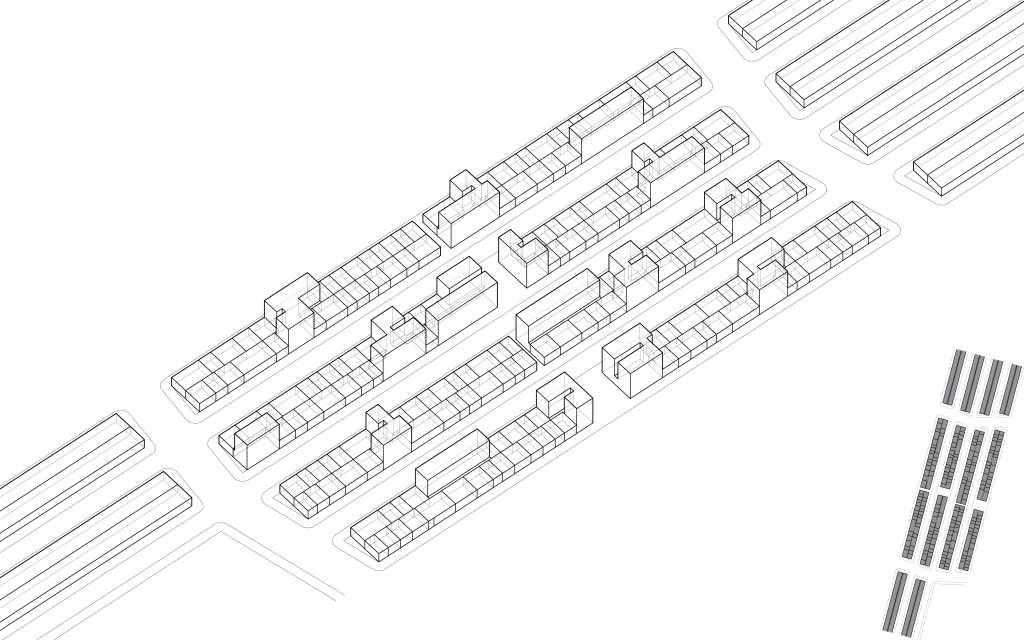

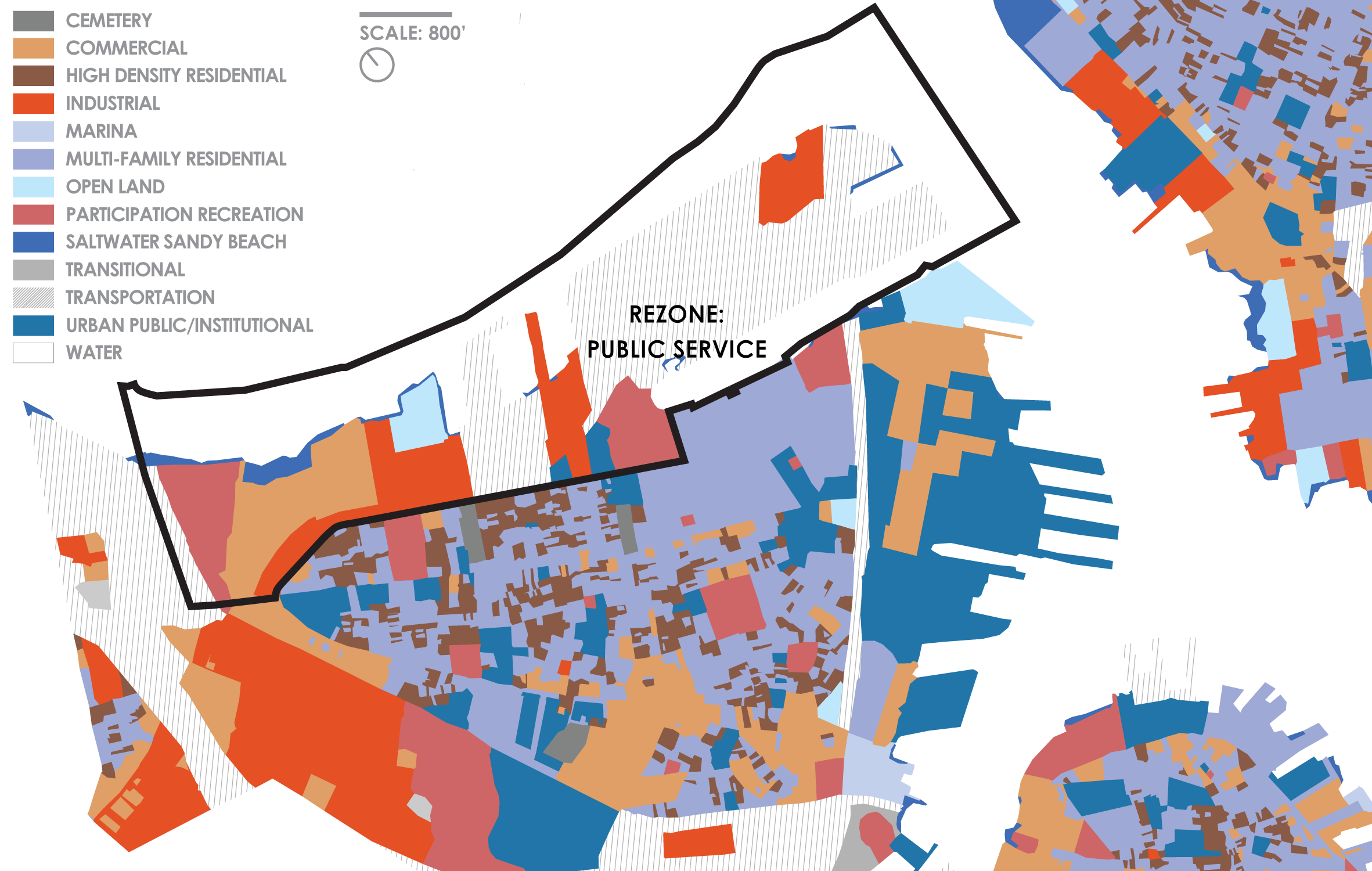

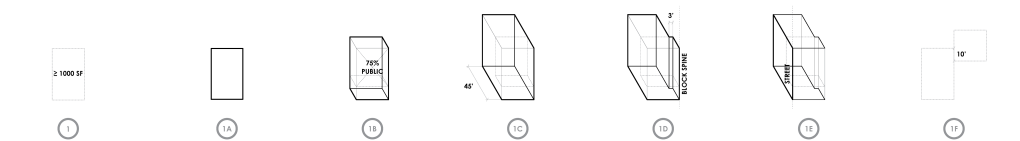

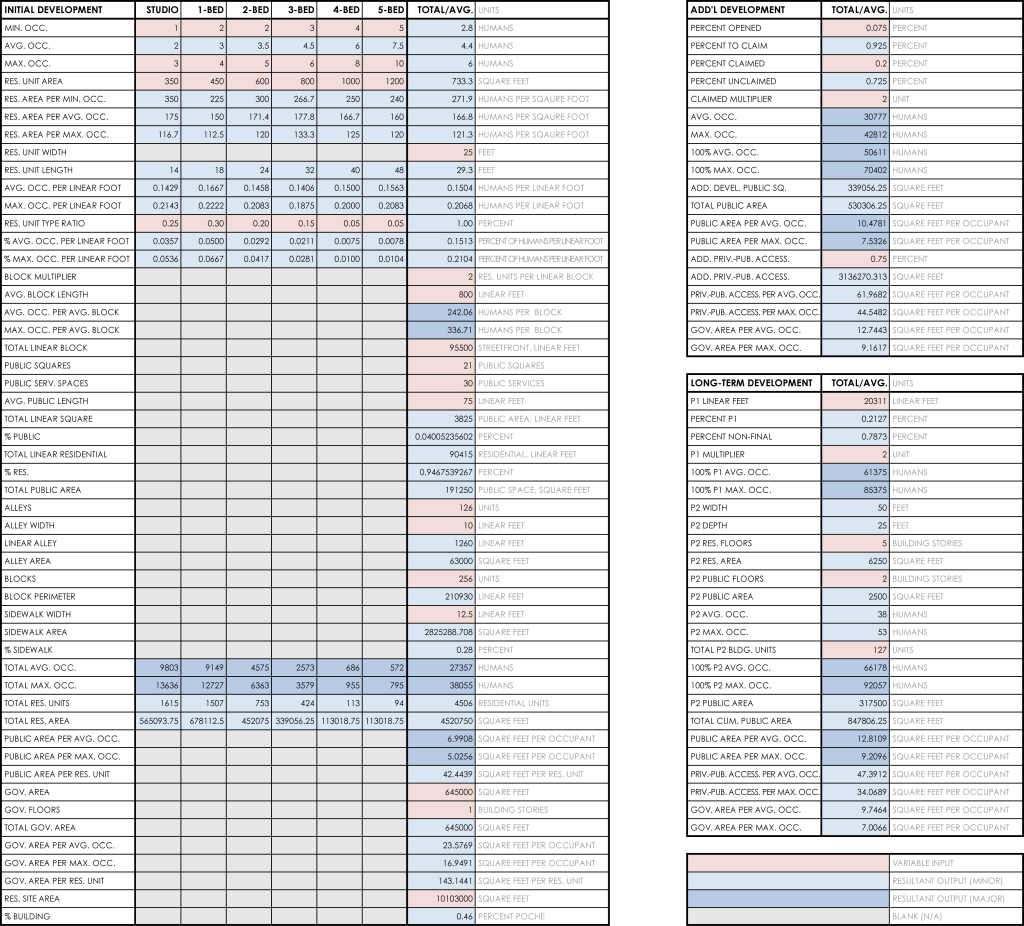

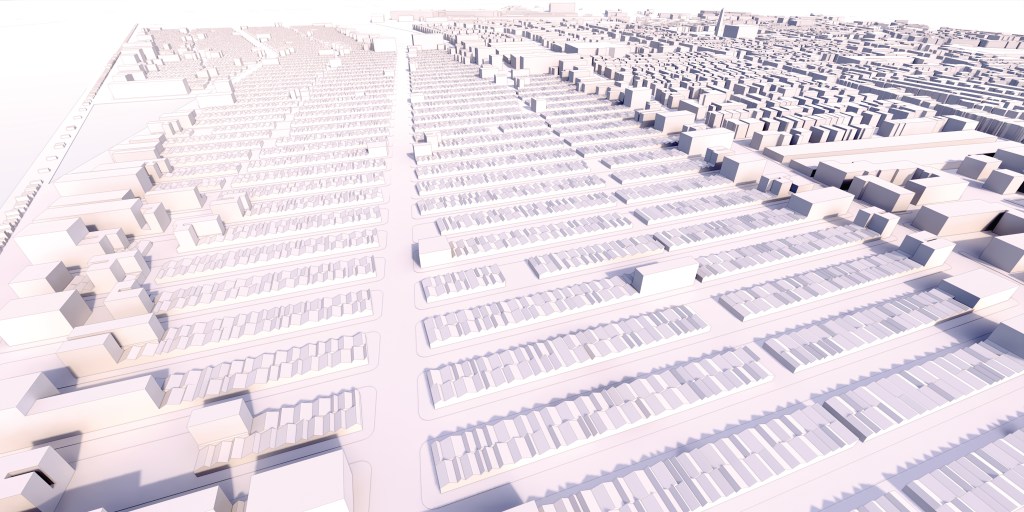

Urban Building Code [Initial Development Regulations: Block System]

The Twenty-First Century Refuge’s urban block system takes cues from the high-efficiency planning of Nineteenth Century Manhattan to produce a layout with almost ten percent greater building coverage. To serve the high volume of incoming humans anticipated, the site is planned for maximum efficiency of construction, and for the initial development phase of the project the site is populated with single-story row houses. The streets are the same width as the 25 feet lot depths to allow space for delivery and installation of the modular units. This dimension is ideal for a nine-foot wide road-roller to prepare in three passes. The site is developed in long strips to accommodate the ideally arduously linear processes of a road-roller.

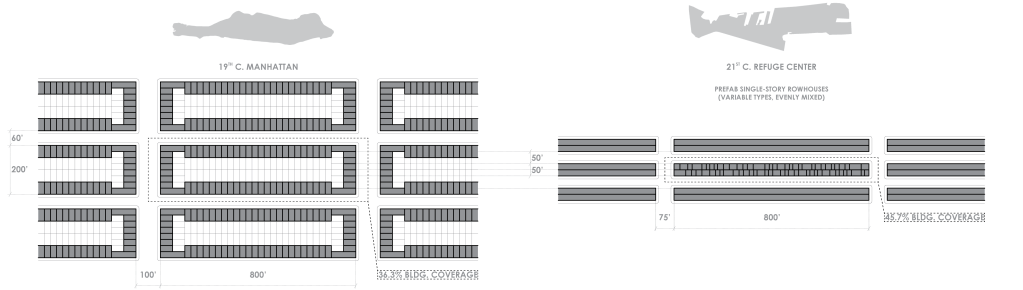

Urban Building Code [Initial Development Regulations: Unit System]

The initial development’s residential units vary in size from open studio to five-bedroom. Their relative quantities are allocated in accordance with anticipated needs, and can be swapped out and moved around as the inhabitants’ demography evolves over time.

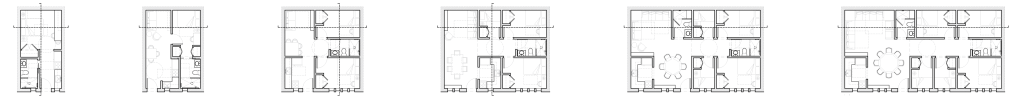

Initial Development Units [Floor Plans]

These residential units are simple and modest, but replete in program. In addition to private bedrooms and bathrooms, each unit is provided with ample kitchen, dining, and living spaces for its intended occupancy. They are assembled from modular components that are prefabricated locally, providing an abundance of working class employment opportunities.

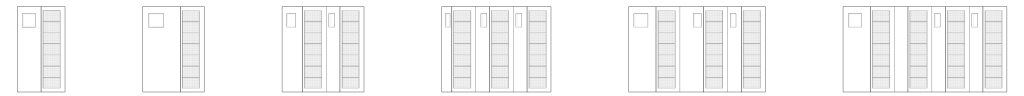

Initial Development Units [Roof Plans, Elevations]

The units’ roofs are gently pitched to collect precipitation to be used in greywater systems. Each gable is equipped with photovoltaic panels on their south-facing slopes.

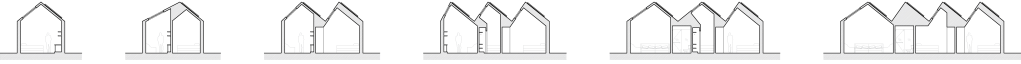

Initial Development Units [Sections]

With only one façade designed to open to the exterior (the other three being party walls), skylights provide natural light to the depths of each unit.

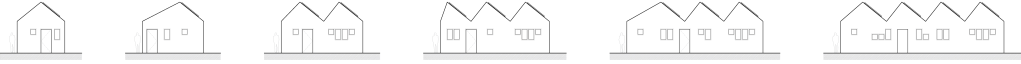

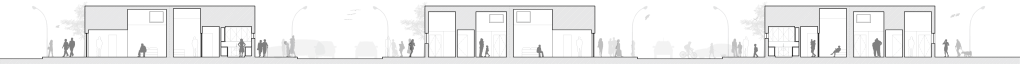

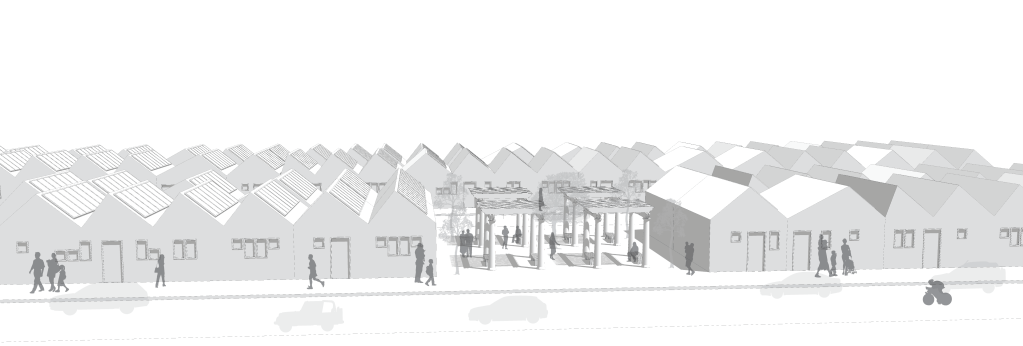

Initial Development Units [Street Elevation]

In their aggregation, the units’ rooflines produce a whimsical and somewhat randomized jagged profile from the street level.

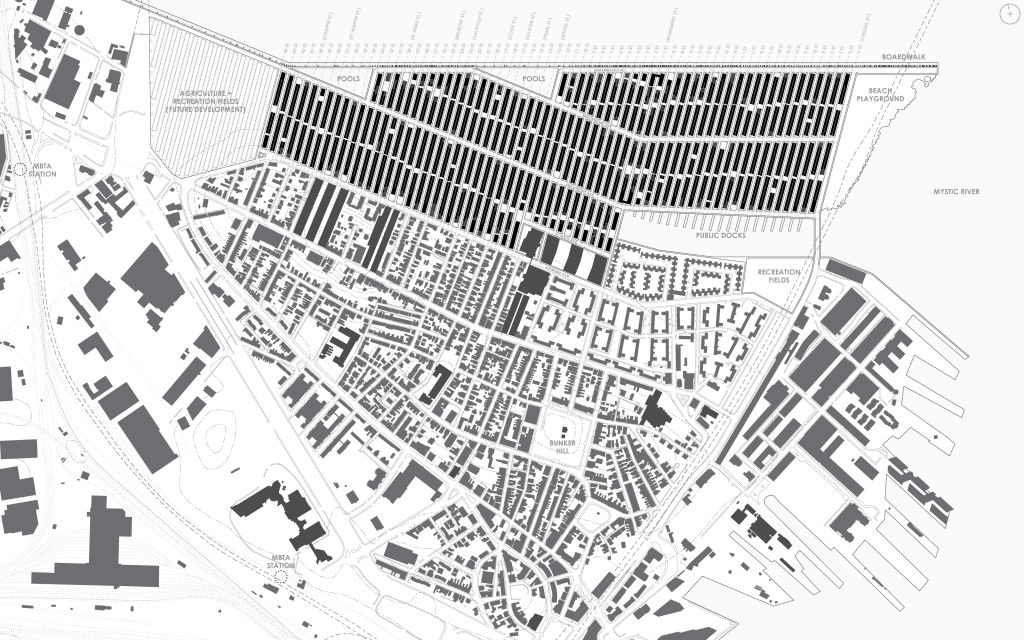

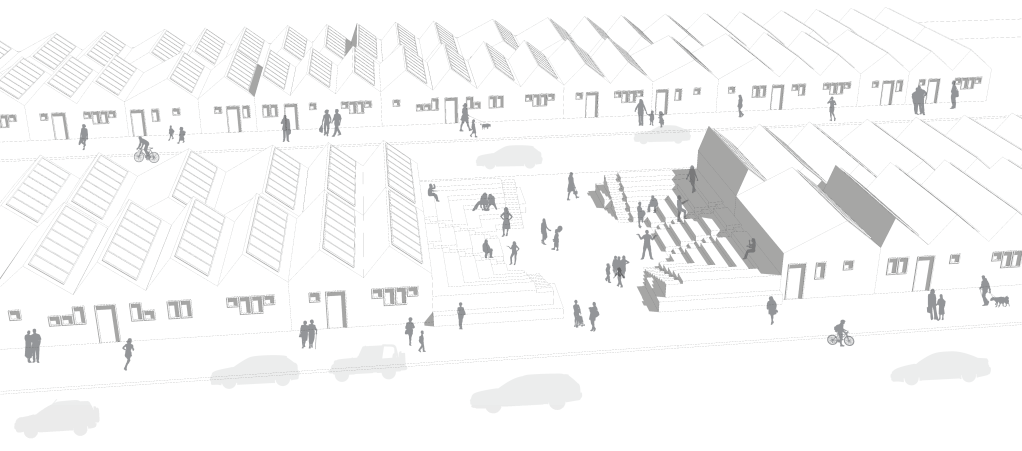

Site Planning [Neighborhood Block Composition]

The residential blocks are interspersed with buildings for providing public social services, and open parcels for outdoor recreational spaces. Each linear block is broken down the middle of its length by an alley that can be further widened to produce additional outdoor space. Major avenues are lined with trees planted at the terminus of each street block.

Site Planning [Initial Block Development]

The orientation of the blocks’ grid system is an extension of the axis of Monument Street (also referred to as “1st Street” within the Refuge) which terminates on the Bunker Hill obelisk, connecting the Refuge — both literally and metaphorically — with the deep historical lineage of its location. The Refuge’s high-density small-scale blocks contrast with the relatively expansive and large-scale layout to the south. With a population of less than 20,000, the existing Charlestown neighborhood will double or even triple in size in a short period of time. The community as a whole will require strenuous investment in order to bolster its existing public social services and aid the local residents in adjusting to the drastic cultural and environmental changes that will occur.

Site Plans: Building Demo // Site Prep [Plug-and-Play Plumbing and Sewage Lines, Rat Slab, Slab-on-Grade]

After demolishing the site’s existing buildings and grading the cleared land, plug-and-play plumbing and sewage lines are buried, an expansive rat slab is poured, streets and sidewalks are established, and slab-on-grade foundations are constructed.

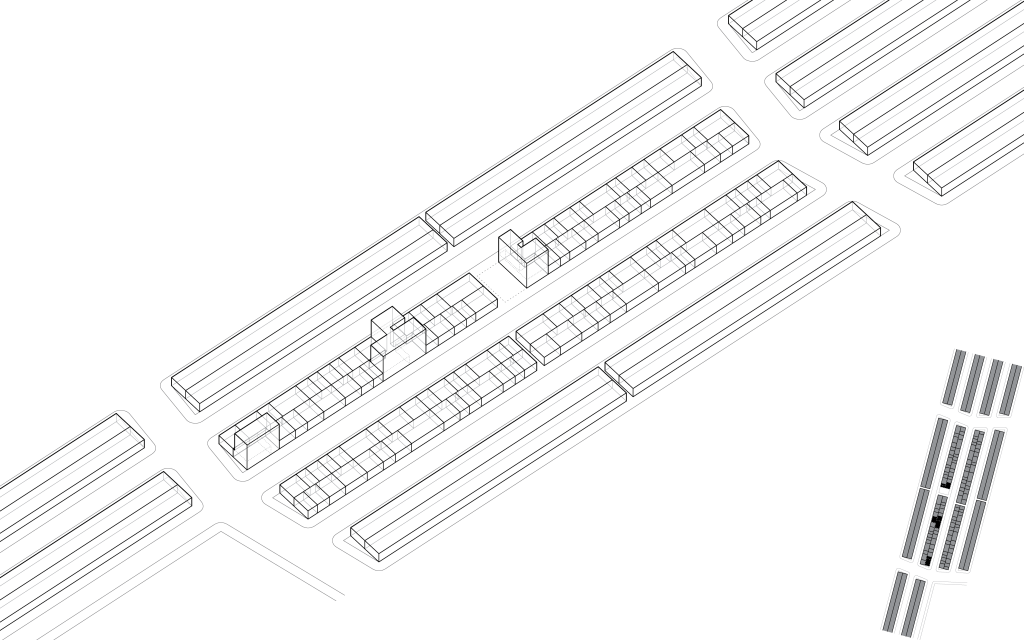

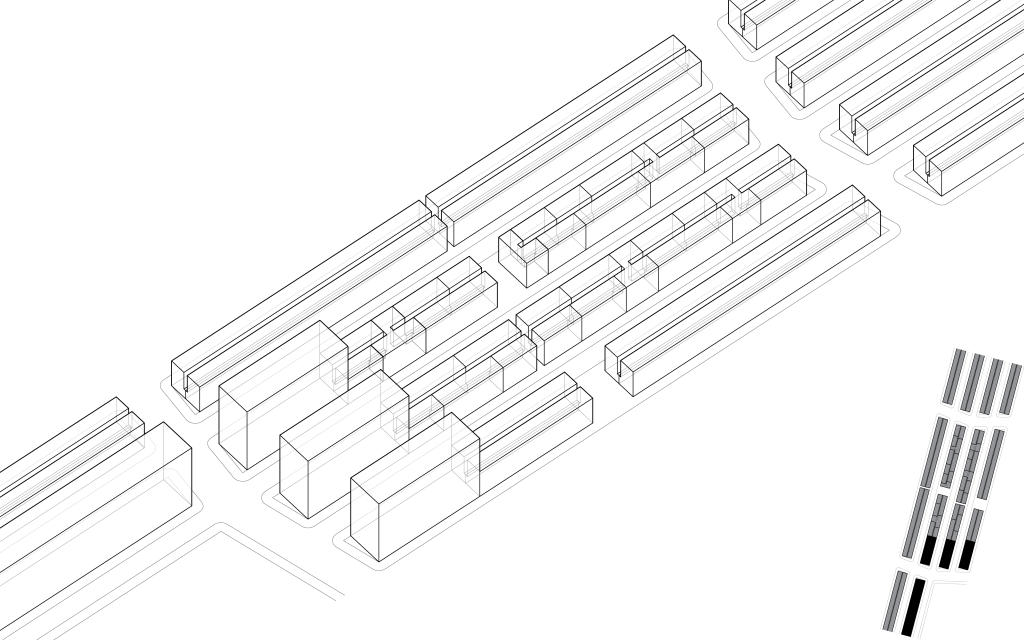

Urban Building Code [Additional Development Regulations]

Building code regulations for additional development encourage inhabitants — no matter their country of origin — to settle down and productively invest in the community of the Refuge, speckling personal and private forms of property ownership and business operation into the publicly owned and managed urban fabric over time.

- 1. When a lot (or combination of lots) greater than 1,000 square feet is occupied by a financially capable party [or when a lot remains unoccupied for a period greater than 3 months], the property of the lot(s) can be claimed [through either purchase or low-rate, long term mortgage] by the occupant [or occupant(s)s of the community] and redeveloped, under the following applicable conditions:

- 1A. The ground floor of the building(s) must fill the extents of the lot(s).

- 1B. Greater than 75% of the area of the ground floor must serve the public, socially and/or commercially.

- 1C. The building(s) must have 2 additional stories above the ground floor, at a height of 15 feet per floor. Coordinate floor-plate elevations relative to 2017 sea level with civil engineers.

- 1D. Along the urban block’s spine (at the lengthwise edge of a lot), the additional stories of building(s) must have a minimum of 3 feet of clearance from adjacent non-contingent lot(s). This will maintain 6 feet of clearance for light and air down the center spine of the urban blocks.

- 1E. The buildings’ envelope along the urban block’s outer edge must meet the buildings’ lot lines to maintain a continuous urban street-front. The building’s envelopes perpendicular to the street and adjacent with non-contingent lots shall be prepared to serve as a party wall for future adjacent development.

- 1F. When a combination of lots crosses the urban block’s spine, there must be a minimum length of 10 feet of adjacency along the length of the spine to connect the lots.

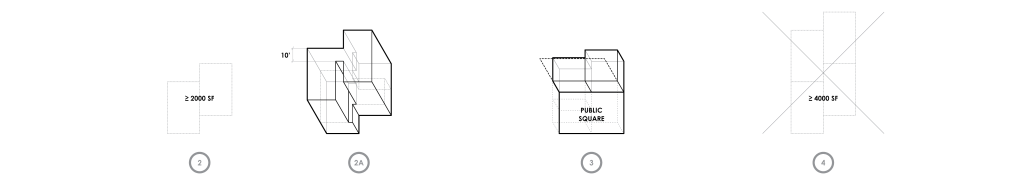

- 2. When a combination of lots greater than 2,000 square feet is redeveloped, both the aforementioned conditions, and the following conditions apply:

- 2A. The upper floors of the building(s) must occupy less than 90% of the area of the combined lot footprint, and maintain 6 feet of clearance down the spine of the lot where possible. If this is not feasible, the building’s connection across the urban block’s spine should be no greater than 10 feet wide.

3. When a quadrilateral aggregation of lots is left unoccupied and unclaimed for a period greater than 12 months, the residential units on the lots can be removed to create a public square. Lots adjacent to public squares may be claimed and converted into service space, following the above aforementioned codes, and creating an urban frontage on the square.

4. No single combination of lots greater than 4,000 square feet may be redeveloped by a single party.

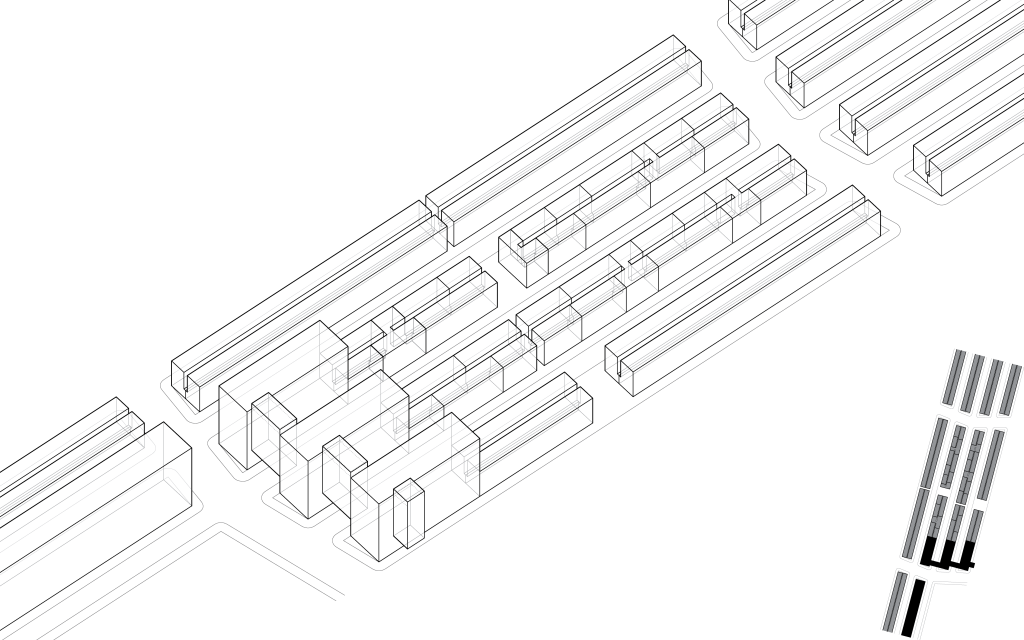

Urban Building Simulation [Additional and Long Term Development]

These regulations also serve to further increase the Refuge’s density: in population, in services, in commerce, in cultural activity, etc. If this kind of development occurs optimally, as the population of the Refuge increases the quantity of publicly accessible space per occupant will increase in corollary. The diagrammatic sequence shows the initial development project housing an average 28,000 to 39,000 occupants and providing about five to seven square feet of service space per occupant, then hypothetically growing over time to a state of dense additional development to house an average 61,000 to 85,000 occupants and provide about nine to thirteen square feet of service space per occupant. Under the additional and long term development regulations, when the population doubles, the publicly accessible space also doubles.

Initial and Additional Development Calculations [As shown in proposed Site Plan]

Site Plan: Proposed [With Additional Development; Solar Angle on June 9, 2017, 3:00 pm]

The site plan shows the Refuge at a stage in its evolution in which the initial development phase has completed, and additional development has begun to modify the project’s fabric.

At the macro level, the Refuge is well supplied with communal amenities. To provide public education for both the incoming and local residents, three large new school buildings are constructed in the southern center of the Refuge. A center for administrative coordination and additional services is housed in a renovated existing building adjacent to the schools. An area of land to the west is left undeveloped to serve as amateur agricultural and recreational fields, to be populated with additional blocks of buildings in the future as needed. The north edge of the development is a long recreational boardwalk, lined with food trucks, carnival shacks, and small sheds for boat storage. The boardwalk encloses two large swimming pools of river water for public use. To the east, a large area of shoreside land is left open as a communal beach. A small inlet to the south is populated with large public docks for ferry transportation.

Perspective Renderings [Open Lot(s): Public Use]

Open parcels of outdoor recreational spaces are coordinated and programmed by the democratic committees of each micro-neighborhoods’ local inhabitants. Public funds are provided to transform these spaces to fit the inhabitants needs and preferences, whether that be a throughway, a garden courtyard of shaded pergolas, a children’s playground, a public square, a community amphitheater, etc.

Montage [Bunker Hill]

The view from a future upper-story residential unit on Monument Street connects the inhabitant with the historical monument of the Bunker Hill obelisk, an icon of the American fight for independence. For a country built on genocide, slavery, and imperialism, the Refuge is a miniscule reparation.

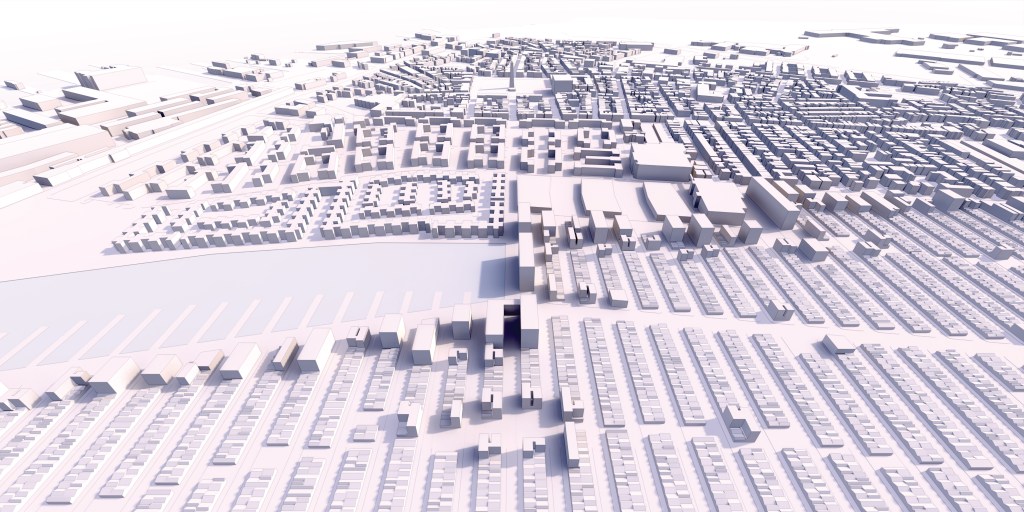

Aerial Perspective Rendering [Looking northward, at the Charlestown Peninsula]

Aerial Perspective Rendering [Looking eastward, down Beachfront Avenue]

Aerial Perspective Rendering [Looking southward, on axis with Bunker Hill’s Monument Street]

Aerial Perspective Rendering [Looking westward, showing diverse ribbons of urban fabric]

- Digital media: Excel, AutoCAD, Rhino, Grasshopper, Enscape, SketchUp, Ai, Ps

PROJECTS: ABODE // CABIN // SEMI-SUB-URBAN // STATION // GREEN // TRANSPOSITORY // TEA-CRETE // LIGHTS // PENDANT // RINGS // NEO-CAIRNS // THESES: METAMATERIALISM (Human Being) // POST-MORDIAL (MIT SMArchS) // ISOTOPIA (Syracuse BArch) // HUMANS: KRIS // JODY

© Human Being Design 2025