Artifacts of Esoteric Embodiment by Kris Menos

Human Being Architecture (Unsited)

MIT SMArchS Design Thesis

Advisers William O’Brien Jr. + Mark Jarzombek

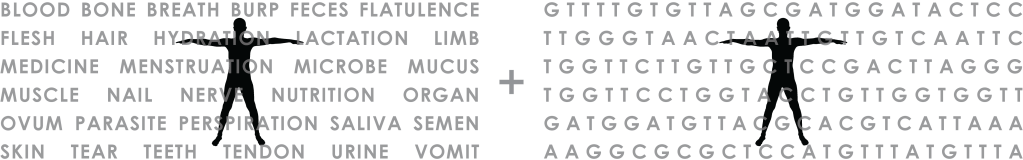

This thesis explores the notion that the membrane of the human body serves as an increasingly inadequate description for the extents of human being, and situates architecture as a mediative apparatus between organism and environment.

This thesis proposes that the discipline of architectural design — as an enterprise of plastic experimentation that embraces emergent technological paradigms, instruments, and armatures — is equipped to explore and express these extents.

VIEW THE PROJECT DOCUMENTATION IN FULL

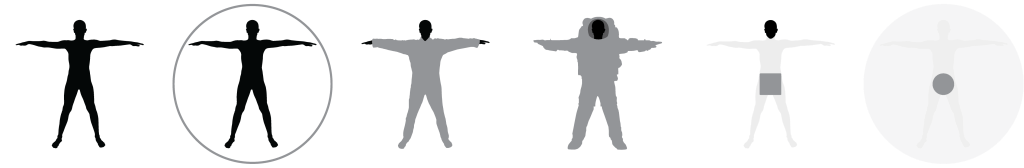

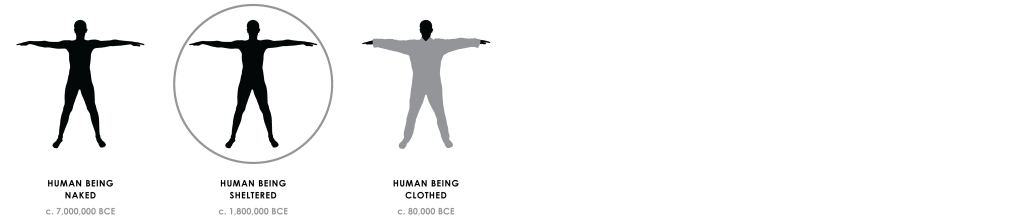

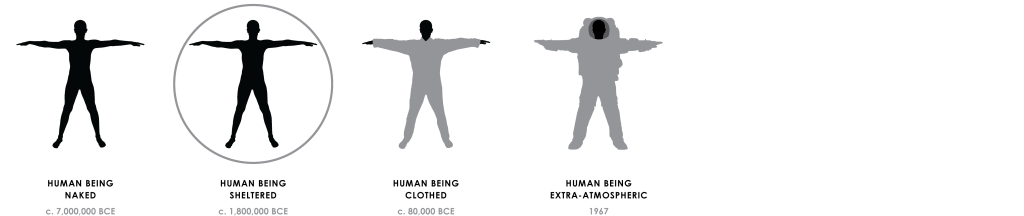

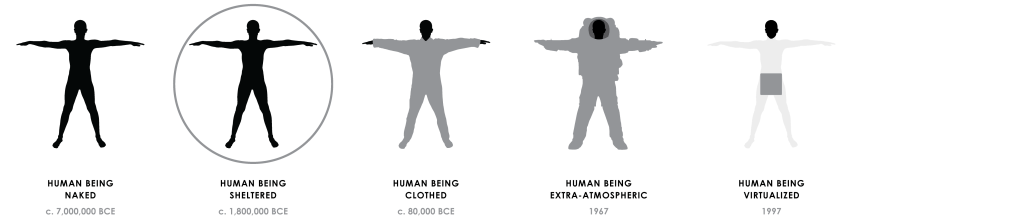

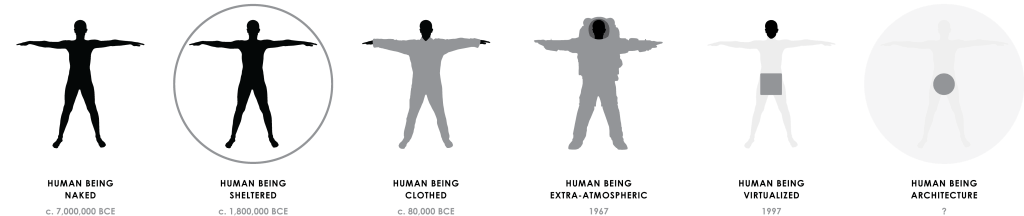

The following diagram maps out continuously expanding notions of human corporeality in architectural design discourse, pointing to several moments in the discourse where humans have been enabled to rely decreasingly on the membrane of the human body through the absorption of new apparatuses and methodologies into the discipline.

Contemporary archaeological discourse places the origin of the hominin (previously referred to as ‘hominid’) to approximately seven million years ago, with Michel Brunet’s archeological team’s 2002 discovery of “Toumaï,” the Sahelanthropus tchadensis found in the central African nation of Chad. In The First Human: The Race to Discover Our Earliest Ancestors, Ann Gibbons (Science magazine correspondent on human evolution) summarizes the rationale for this attribution: “Teeth and skull show ‘human’ features, and possibly signs of upright walking.” (Gibbons xii-xiii) This delineation in evolutionary lineage — however (arguably) arbitrary — marks a potential beginning point for our story, for the story of human being.

Human being walking (maybe). Human being talking (maybe). Human being naked.

In Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective, Mark Jarzombek (Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture at MIT) describes “the earliest evidence so far of a man-made structure,” approximately 1.8 million years ago at the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania: “a circle of lava stones that were the remains of a hut or windbreaker consisting of branches anchored at the base by stones piled into heaps and spaced on the circumference about every 0.7 meters.” (Jarzombek 3) Presumably constructed to supplement the human body’s membrane for purposes of climatic comfort and protection, this location symbolically marks the beginning of conscious human intervention with the environment through “social order and spatial differentiation,” and the ongoing enterprise of homo faber for the purposes of bodily wellbeing and satisfaction. (4) The structure — and its surrounding locale, which is scattered with a wide range of stone tools and other human artifacts — might also be viewed as a signpost for the foundation of cultures of toolmaking technē, design methodology, and ontological construction; the inauguration of architectural design discourse.

Human being cultured. Human being mindful. Human being sheltered.

In the Journal of Archaeological Method & Theory, Ian Gilligan (Department of Archaeology at the University of Sydney) postulates, through an analysis of Paleolithic tools and human migratory and thermal models, “The Prehistoric Development of Clothing” as beginning approximately one hundred thousand years ago. (Gilligan 32) The author defines ‘clothing’ to “denot[e] items that act to enclose or cover the body,” and situates its development as a part of the larger technological shifts in human capacity that enabled human populations to expand, and migrate into less climatically temperate geographic regions. (17) The advent of clothing would further decrease the human reliance on the membrane of the body, in order to adapt to relative changes in environmental conditions. The mission of the architectural design discourse took on mobile, nomadic, and increasingly transformative — or ‘dominion-ative’ — aspirations.

Human being active. Human being capable. Human being clothed.

In 1967, the discursive entity of architecture again expanded its role through another shift in paradigm: the cover for the February issue of Architectural Design featured an image of a human spacesuit. (AD37 cover) The discipline of architecture now encompassed the motivation for the human body to survive not only within the atmosphere of the planet, but also in the vacuum of space outside of it. This new instrumentation almost altogether augmented the body’s membrane, adequately simulating the necessary atmospheric conditions under which the human body had previously evolved. As a technological armature for preserving the pre-existing environment of the human body and catering to its ‘natural’ functions, the spacesuit fits comfortably within the discourse of architectural design, continuing the territorial expansion of humankind into previously impossible domains.

Human being extra-human. Human being otherworldly. Human being extra-atmospheric.

In 1997, another sea change quietly occurred. The New York Stock Exchange commissioned Asymptote Architecture to design a “Virtual Trading Floor,” a digitally simulated virtual environment. (Amelar 140) Architecture could now exist without being physically inhabited, facilitating human processes without need for the entire human body, but merely its cognitive faculties and interactive appendage(s). Supplanting the direct bodily inhabitation of architecture through simulated spatial experience, the architectural design discourse lost its direct obligation to the human body. This continues to compound through the rise of biomechatronic augmentations for the human body, including synthetic organs and prosthetic limbs, which have effectively reduced matters of mortal concern for the body and its contents.

Human being supplemented. Human being transformed. Human being virtualized.

A desire to transcend the human body is a common characteristic in human beings. Whether through biological programming, environmental conditioning, or individual autonomy, humans seek to connect with each other, to connect with a collective, to connect with something greater, to connect with a higher power, to go on living, to see what the future holds, to continue to exist in some way or another, to see what it’s like, to escape this form of existence, to have another chance, to find new opportunity, to confront their mortality, to be remembered. In many ways, human beings use architecture to facilitate this desire for transcendence and its diverse manifestations, including houses of worship, funerary constructs, and memorials.

In “Architecture as Membrane,” Georges Teyssot (Professor in the School of Architecture at Laval University, Quebec) speculates that a human’s being extends beyond the physical extents of their contiguous body, as a continuously fluctuating architectural membrane. The human body itself is not an adequate membrane, or a comprehensive embodiment for human being. Human beings consume and excrete. Human beings produce and deplete. Human beings procreate and expire; grow and decompose. These phenomena extend beyond the boundaries of the human body, but are fundamental — perhaps inarguably — to human being. Building from Teyssot’s conception of architecture as the membrane for “a continuous, fluid” human, this project positions the discourse of architectural design as an arena to explore, define, and even create expanded notions of human being, corporeality, and selfhood.

This project speculates that the discourse has the opportunity to progress further on this trajectory, to move beyond obligations to the human membrane, to human being architecture, whereby artifacts of human creation can exist as externalized augmentations to an individual’s intellective sense of self-identity. Human being post-corporeal. Human being transcendent. Human being architecture.

- Sarah Amelar, “Asymptote’s Dual Projects for the NYSE Span Both Real and Virtual Realms,” Architectural Record 187 (1999): 140-145.

- Ann Gibbons, The First Human: The Race to Discover Our Earliest Ancestors (New York: Doubleday, 2006).

- Ian Gilligan, “The Prehistoric Development of Clothing: Archaeological Implications of a Thermal Model,” Journal of Archaeological Method & Theory 17.1 (2010): 15-80.

- Mark Jarzombek, Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective (Hoboken: Wiley, 2013).

- M.D. Leakey, Olduvai Gorge Volume 3: Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960-1963 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971).

- John McHale, ed., Architectural Design 37 (1967).

- Georges Teyssot, “Architecture as Membrane,” in Explorations in Architecture: Teaching Design Research, ed. Reto Geiser (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2008), 166-175.

At the figurative intersection — and perhaps literal transition — between human and environ, post-mortem ritual practice is a fertile and potent testing ground for these concepts. As human beings increasingly embrace the paradigms of bioinformatics and digital fabrication, this thesis proposes that alternative funerary practices might emerge to embrace these technologies, reflecting a widening range of contemporary cultural attitudes toward mortality, humanity, and end-of-life ritual. These new tools can provide individuals with increasing levels of both personal and collaborative agency in the design of their own memorial artifacts, and those of their loved ones.

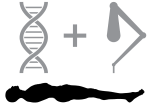

This thesis enacts a hypothetical scenario in which a group of humans embrace their corporeal materiality and its internalized information as precious and sacred, to produce memorial artifacts that are constructed from their own biomatter, and that externalize the otherwise invisible informatic structure of their genetic material.

The design and fabrication of these artifacts is grounded in a study of the use of biomatter and genetic material in contemporary art and design practice, as well as some select funerary practice and memorial architecture.

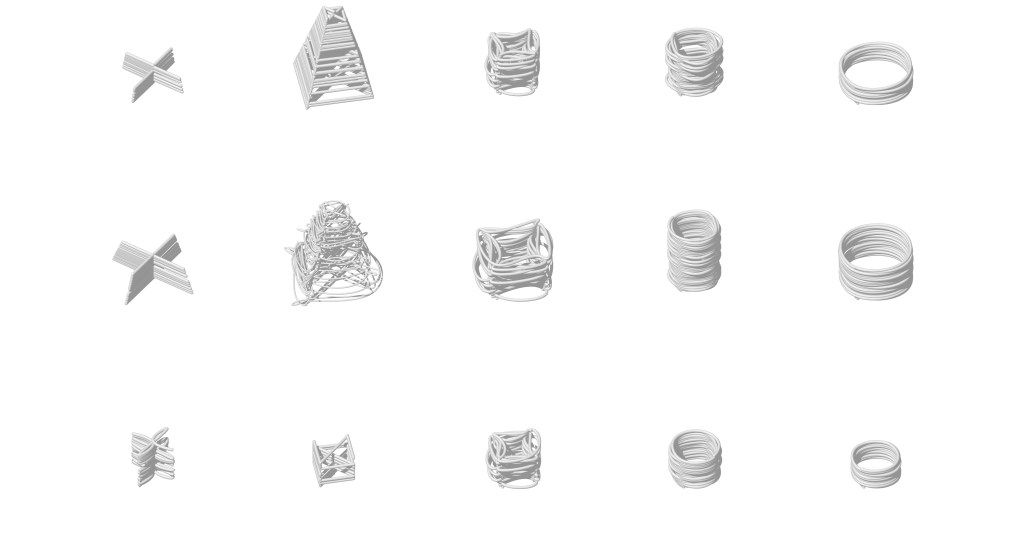

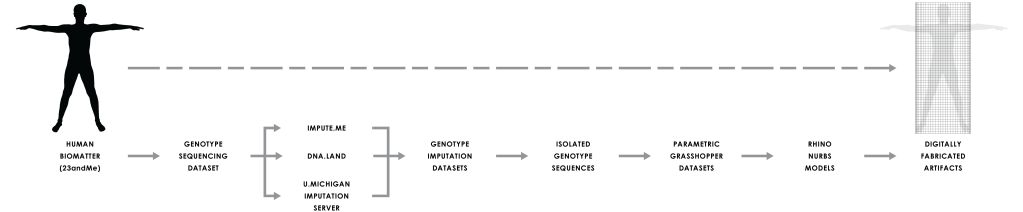

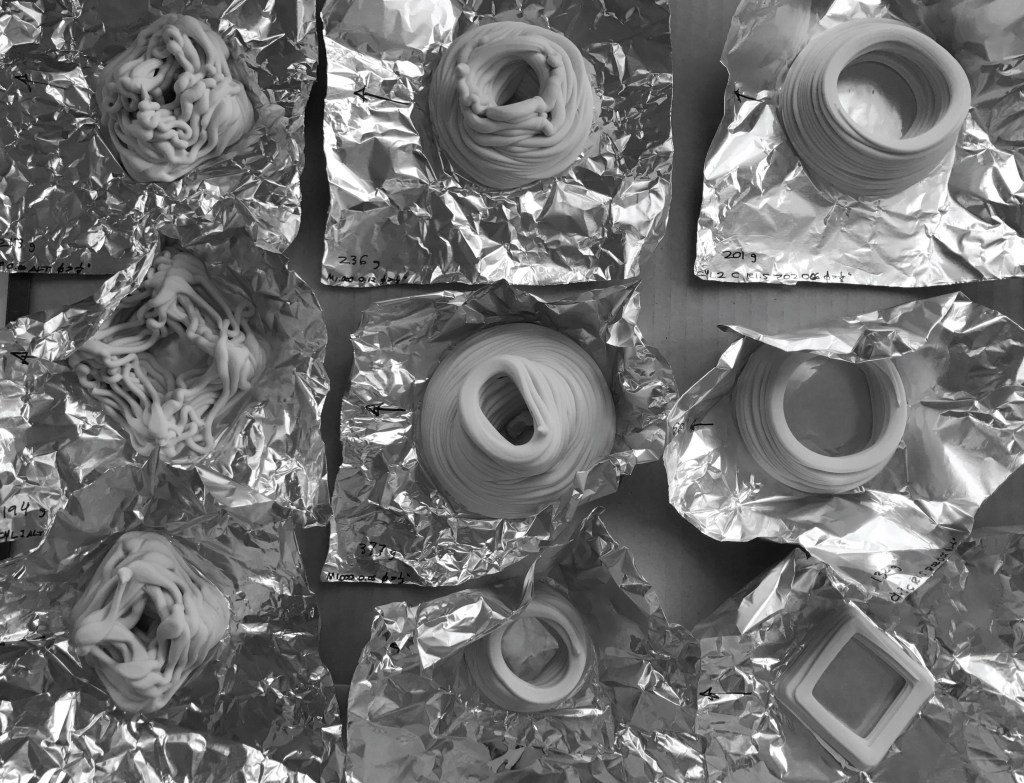

This project develops, in tandem: (A) parametric systems for importing and formally encoding streams of genetic information, and (B) fabrication systems for extrusion printing water-based latex caulk via pneumatic power and CNC tools, using choreographed toolpaths of robotic gestures to produce a series of speculative models.

Within the hypothetical scenario played out in this thesis project, each adherent to this exequial system adopts the task of selecting a specific sequence of their genetic information — either unique to them or universal to humans — and designing a unique translative language for this information, (or selecting a pre-established one, depending on the sect or credence to which they ascribe). As language and medium are inexorably entwined, this process inevitably involves the development (or selection) of fabrication methods and functional parameters for the deployment of this translation.

As with any mode of artifact-making that arises out of a belief system, this project speculates that over time and amongst varying groups, varying attitudes toward the artifacts’ formal translation and material treatment will evolve. This section explores some potential modes of genetic translation and fabrication, and then pushes forward one of these modes.

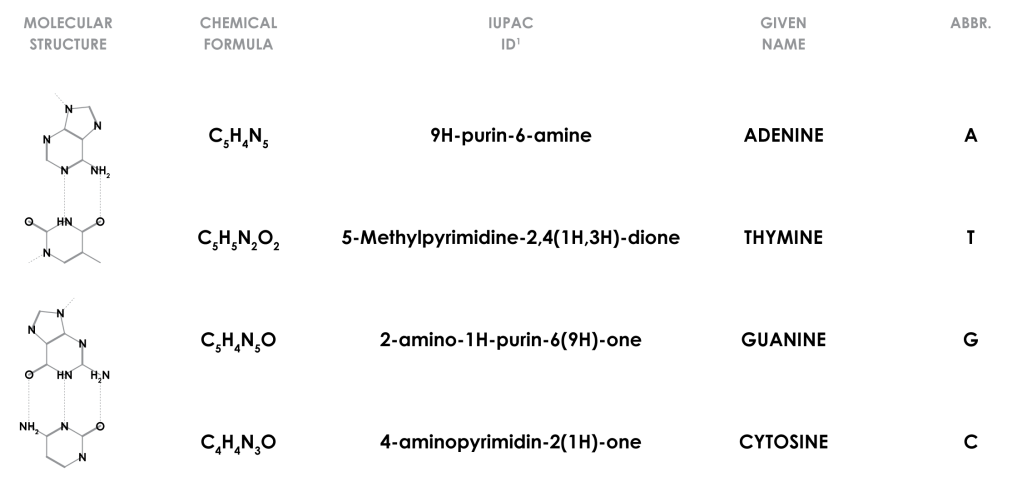

Genetic information is a coded representation of biochemical streams of microscopic matter, making a previously unknown and invisible biological essence accessible to the naked eye through various means of representational description and/or translation.

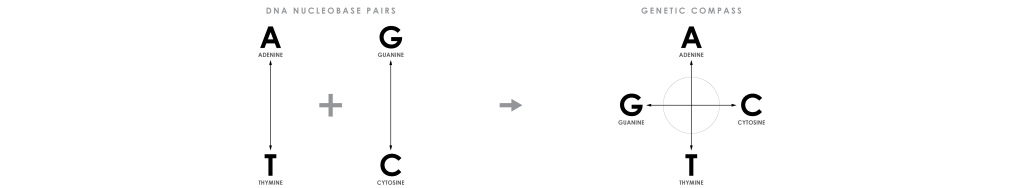

The four nucleobases of DNA, Adenine, Thymine, Guanine, and Cytosine, have been assigned innumerable names and symbols since their respective discoveries throughout the Nineteenth Century, and their formal classifications in the Twentieth, and onto later appropriations by designers, architects, and bioartists into the Twenty-First. The matrix depicts some differing names, codes, and transcriptions that have been applied to the four nucleobases of DNA, from the initial diagramming of their molecular structures, to the definition of their chemical formulas and formal identifications, to their given names and abbreviations A, T, G, C, and common systems of color coding, to finally some translations by various artists and designers.

- 1. IUPAC, “International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry,” IUPAC, https://iupac.org (accessed October 15, 2016).

- 2. Ryan Hoover, “Alba,” Ryan Hoover, http://www.ryanhoover.org/rd/alba.php (accessed October 15, 2016).

- 3. Carl Sagan et al., “A Message from Earth,” Science 175 (1972): 881-884.

- 4. Joe Davis, “Microvenus,” Art Journal 55.1 (April 1996): 70-74. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/777811 (accessed October 15, 2016).

- 5. Joe Davis, “Romance, Supercodes, and the Milky Way DNA” symposium paper, in Ars Electronica 2000 Catalog: Next Sex, ed. Gerfried Stocker and Christine Schöpf (Vienna: Springer Verlag, 2000), 217-235.

- 6. Peter Eisenman, “Biocentrum,” Peter Eisenman fonds Collection, Centre Canadien d’Architecture, Montréal, reference number: DR1999:0646 ©CCA. 7. Sheilah Britton and Dan Collins, ed., The Eighth Day: The Transgenic Art of Eduardo Kac (Tempe, AZ: Institute for Studies in the Arts, Arizona State University, 2003).

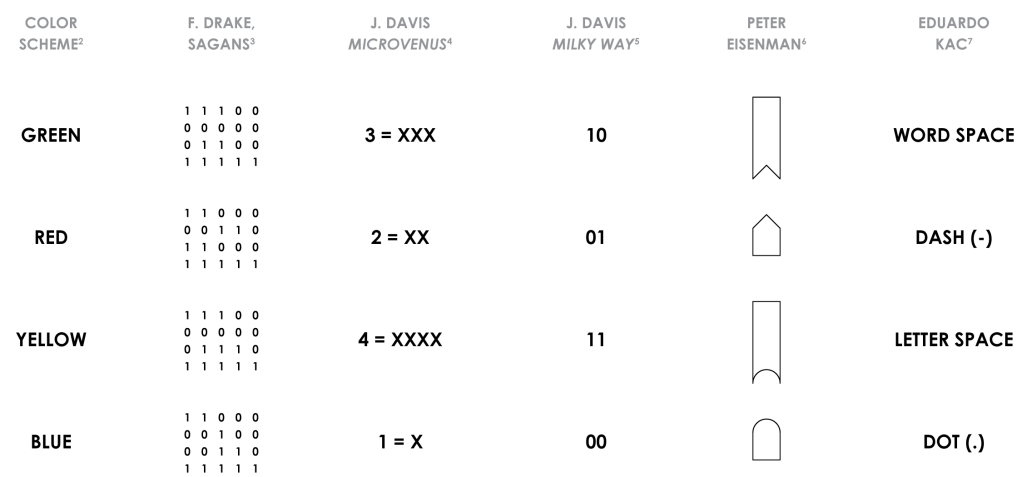

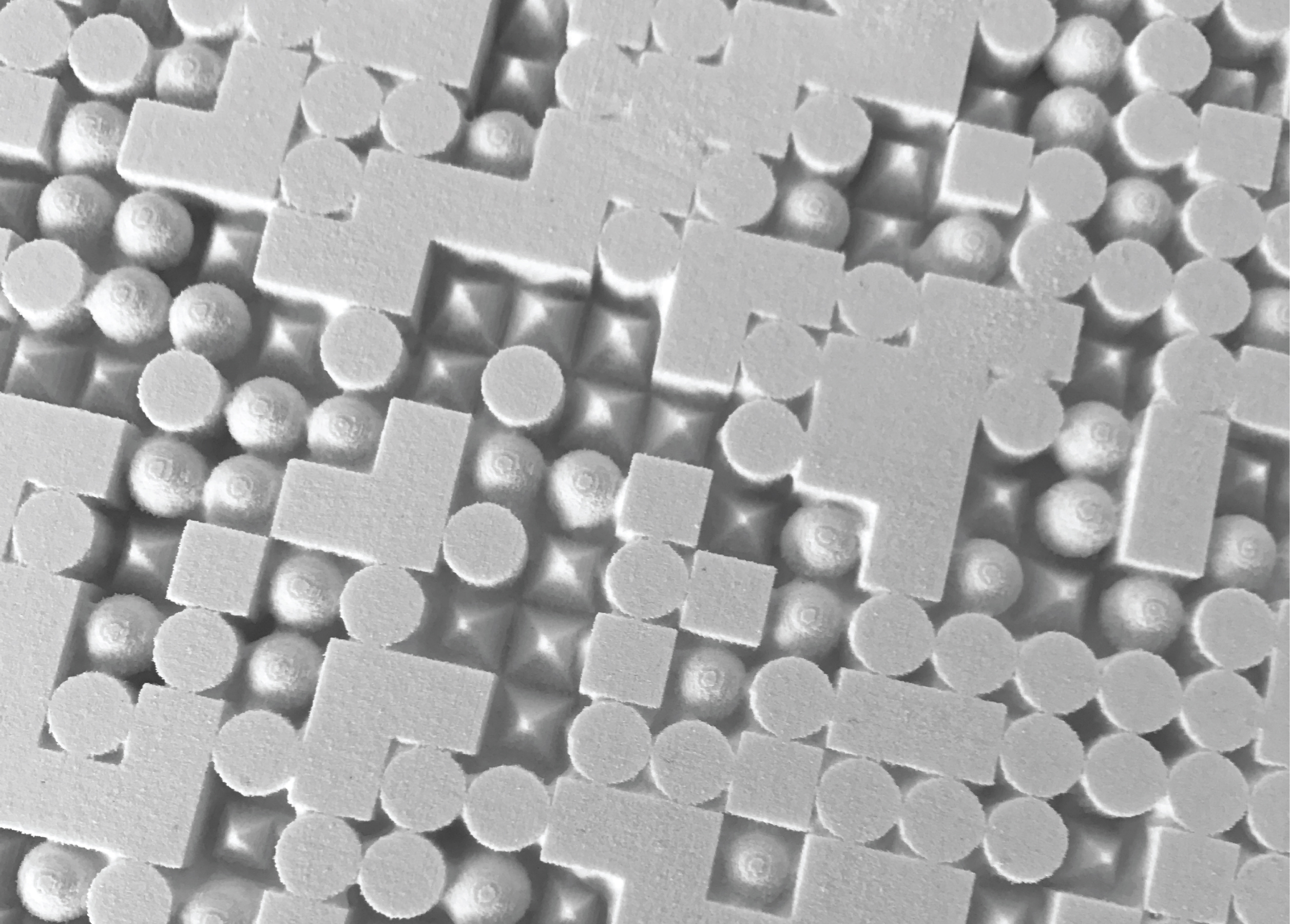

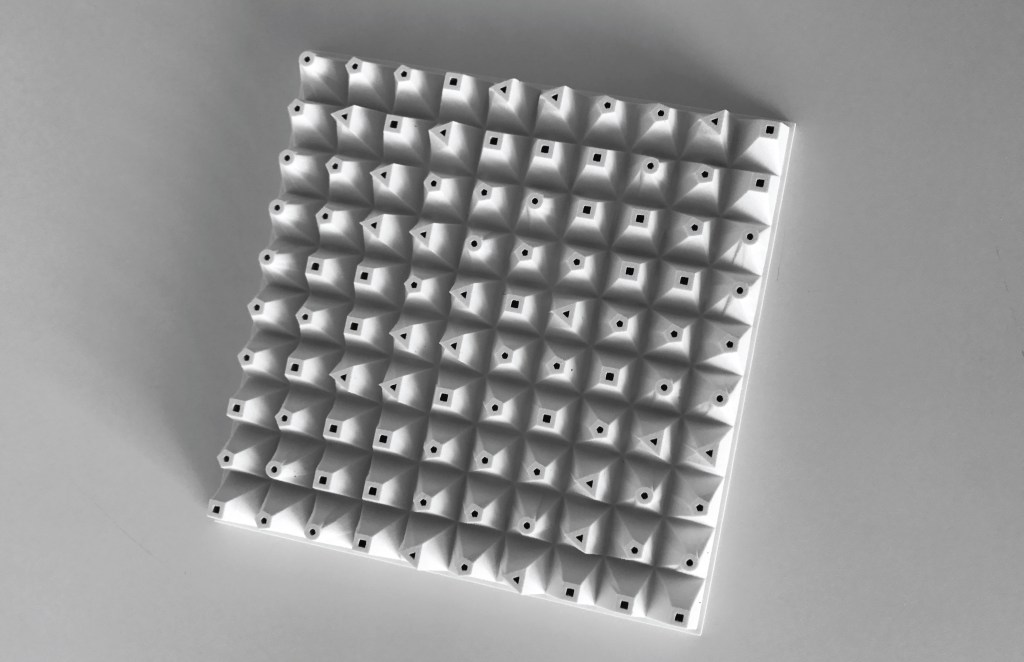

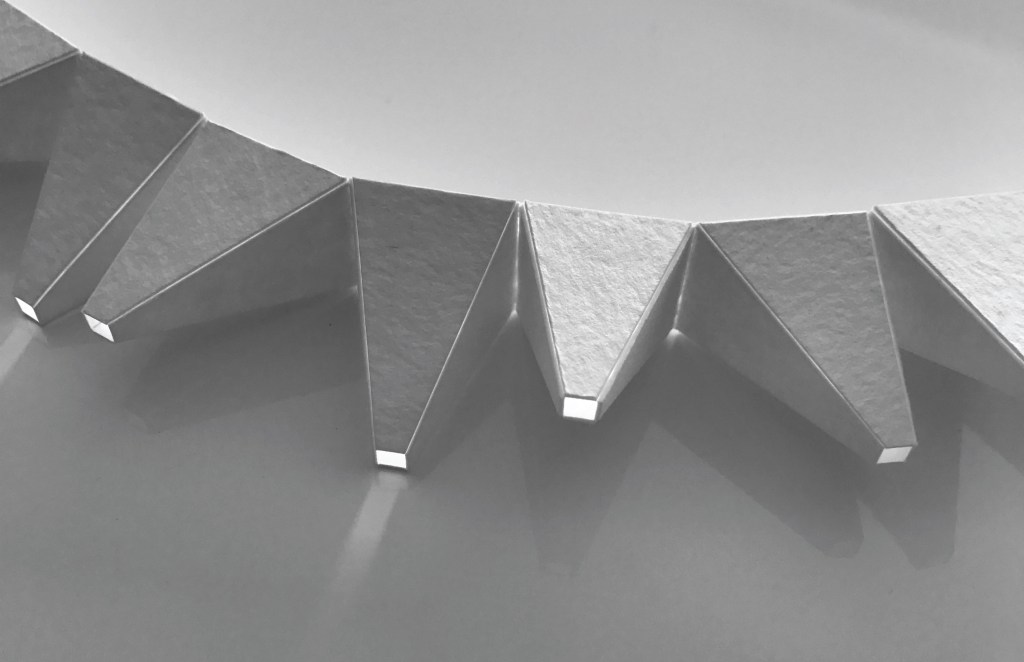

(1) Point-to-Shape-Solid translation for mechanized CNC assembly: a humanist translation of point-streams of genetic information into aggregative formal compositions of basic geometric solids.

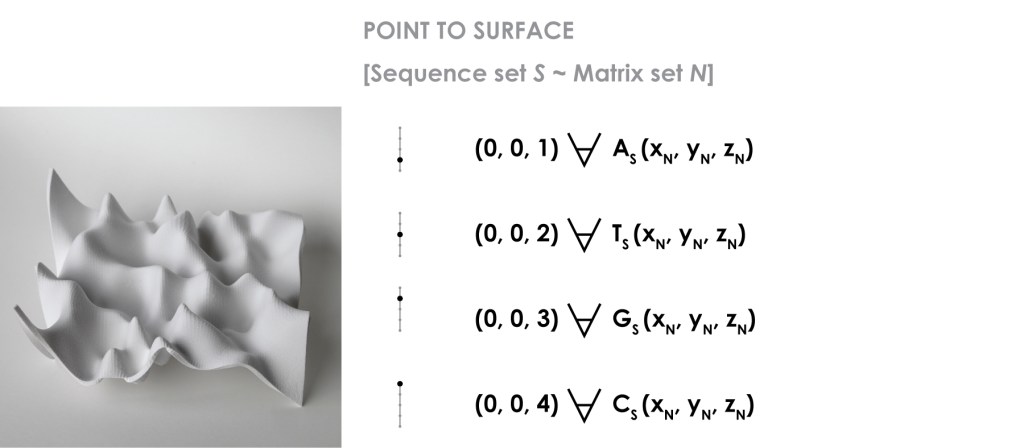

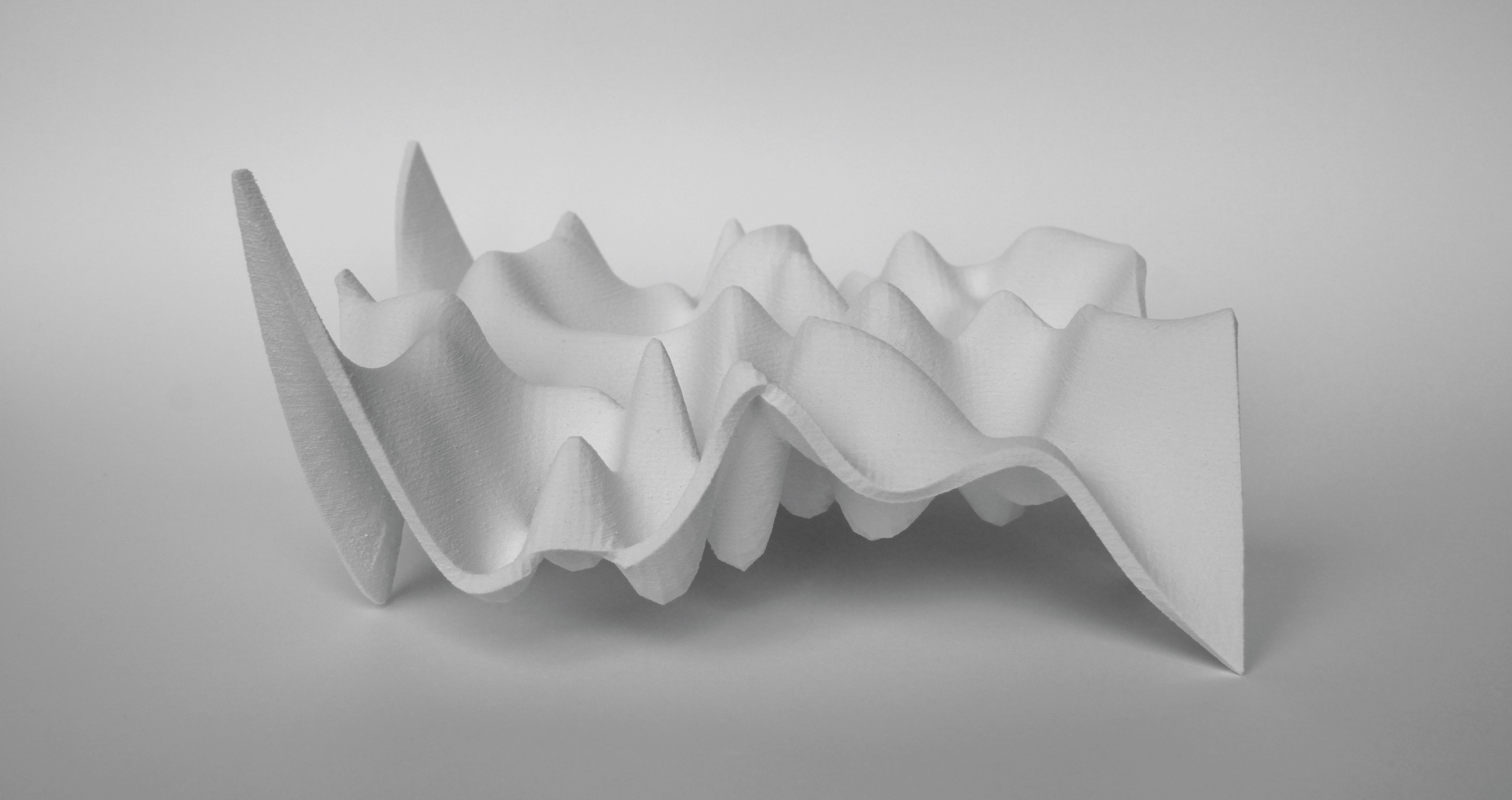

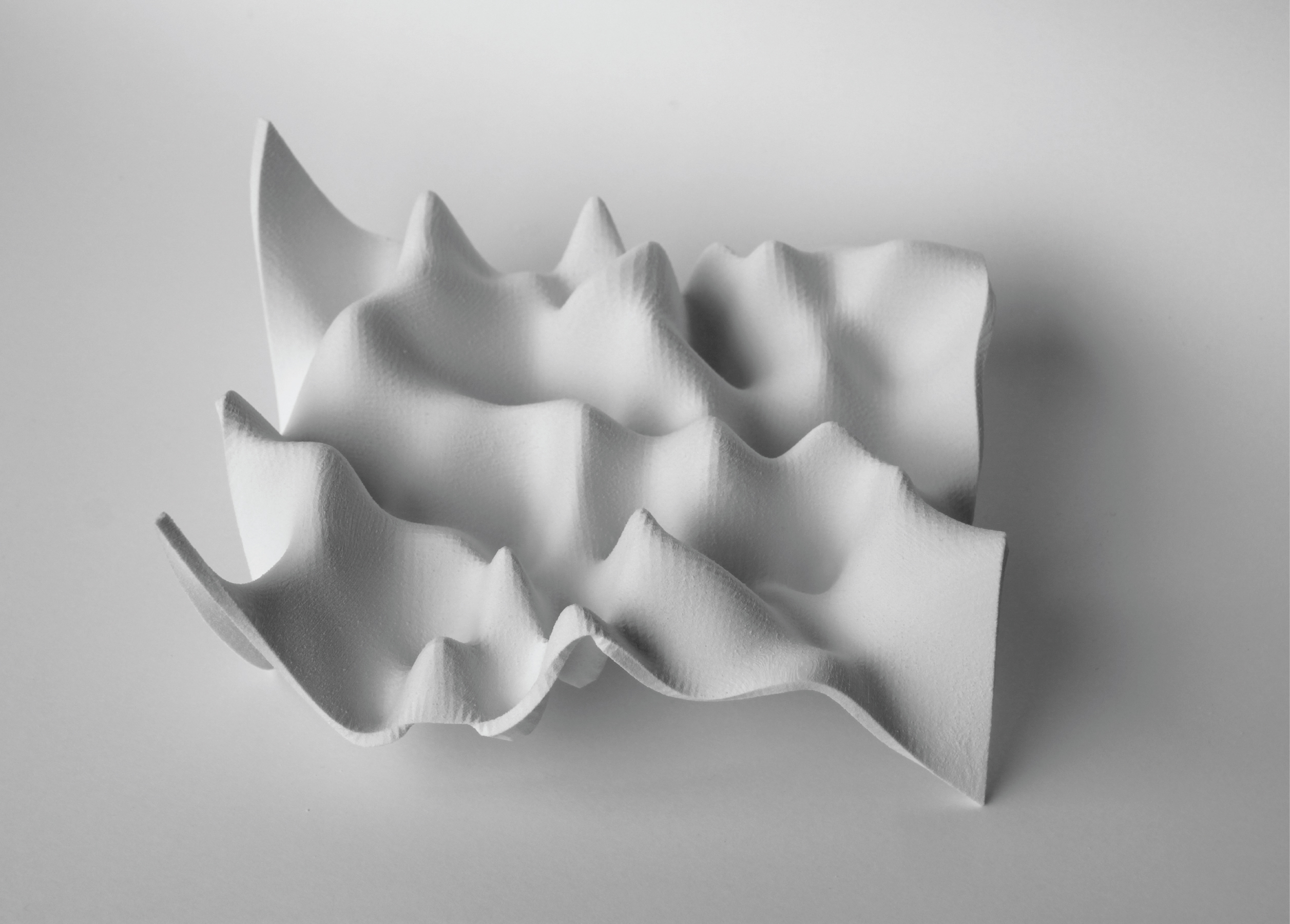

(2) Point-to-Surface translation for subtractive manufacturing: a posthumanist translation of point-streams of genetic information into varying elevations relative to a plane to produce “formless” and “bodiless” undulating surfaces.

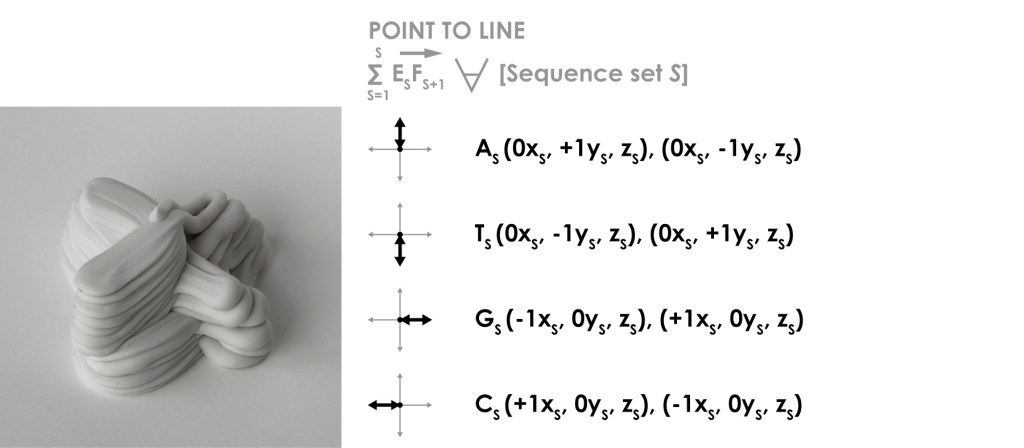

(3) Point-to-Line translation for additive manufacturing: a transhuman translation of point-streams of genetic information into a rule-based parametrically generated choreography of linear extrusion that strives to produce form through movement, but struggles against its material nature.

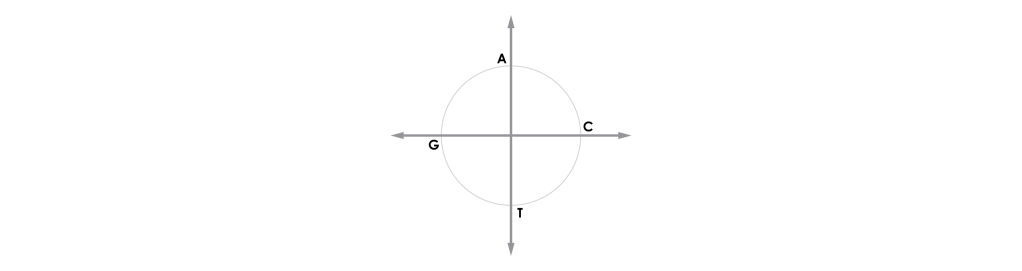

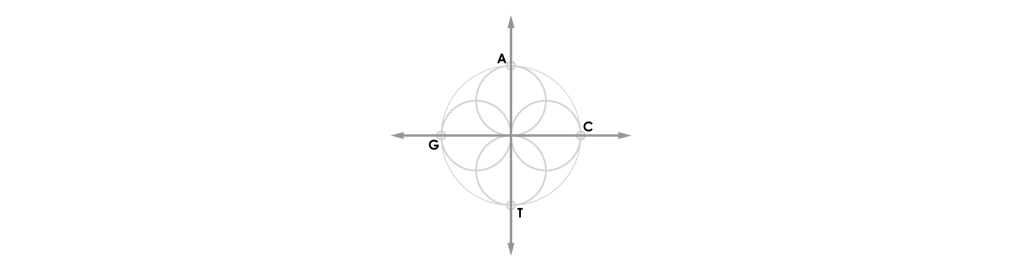

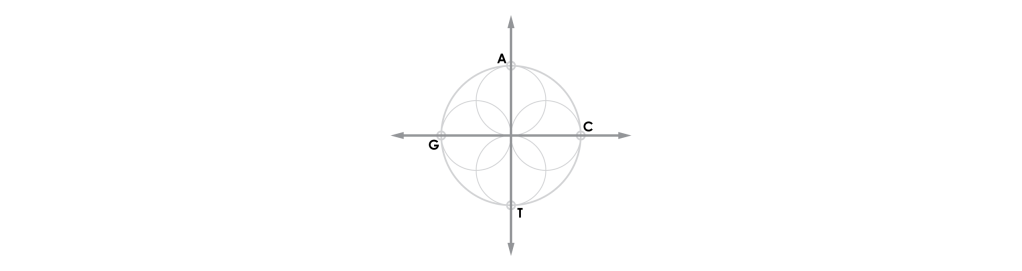

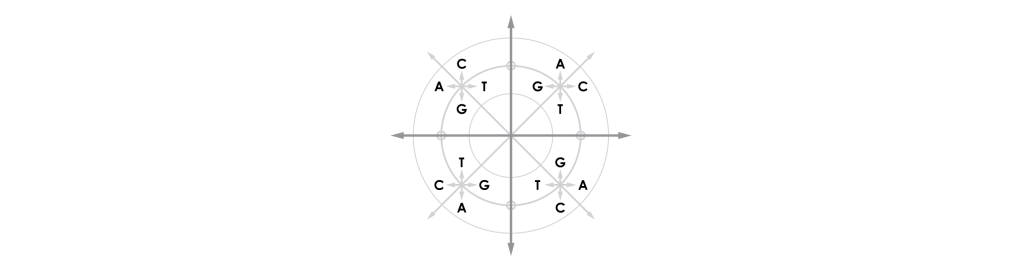

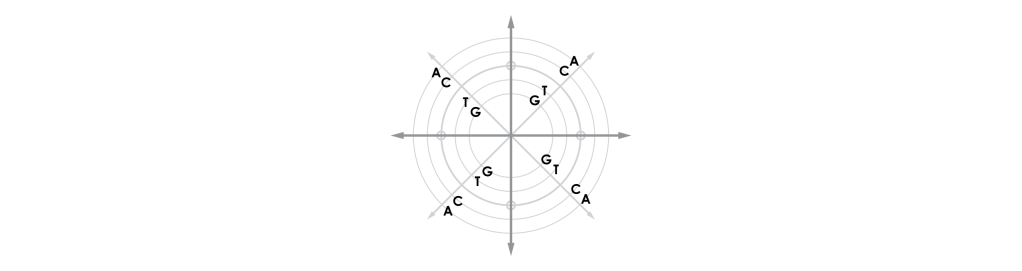

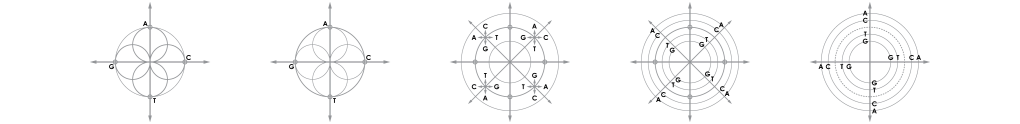

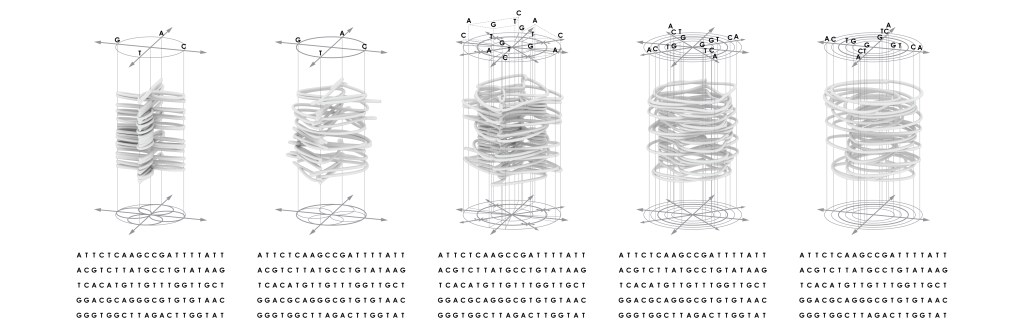

“Point-to-Line” translation is founded on the fictional “genetic compass,” which reconfigures and the paired parallel binaries of the molecular structure of DNA — A-to-T and G-to-C — into binary strands superimposed perpendicular to and overlapping with one another.

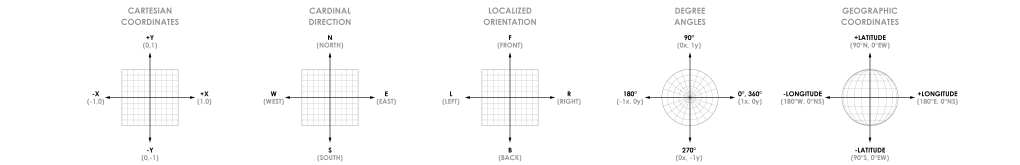

This imbues the microsystems of the DNA nucleobases with a system of macro-spatial organization, aligning the genetic compass with other quintessentially human quadrantal systems of spatial description: the Cartesian coordinates of Euclidean space, with positive and negative X- and Y-axes; the cardinal directions of terrestrial space, with North and South, East and West; the localized orientations of human space, with Front and Back, Right and Left; the geometric angles of degrees and radians, from zero to 360, and zero to 2𝛑; and the geographic coordinates of Earth, with positive and negative Latitude and Longitude. These kinds of axial, quadrant-based systems of spatial orientation exist in other systems of orientation and cultural belief, including: the 12-hour face of the modern timepiece, the layout of the four suits of Western playing cards, and the crucifix form of the Christian Trinity.

The genetic compass joins these systems as a newly-formed cultural belief system, a quasi-religious framework for a ritual ceremony that encodes information as matter placed in space. The axial format of the genetic compass and the linear structure of genetic information are particularly compatible with the multi-axial, temporally-bound articulation of the robotic fabrication arm. The compass serves as the basis for a series of CNC toolpaths, guiding sequences of choreographed gestures that follow the rhythm of the information input, and each experimenting with various techniques for material buildup and mounding.

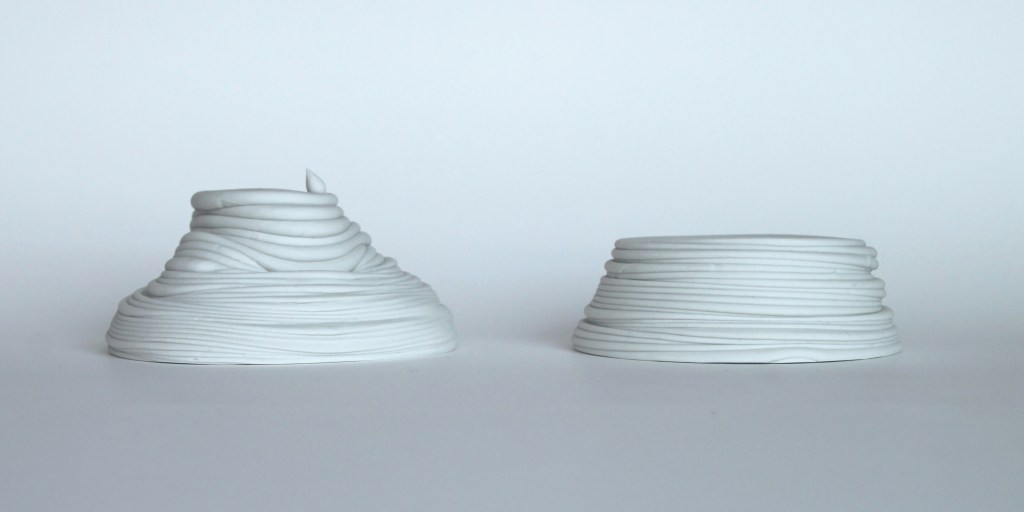

Through this ritual practice, the theoretical cultural construct of the genetic compass permeates the ethos of its adherents, as a potent icon with existential implications. The primary series of speculative memorial artifacts produced for this thesis project use “Point-to-Line” translation for extrusion-based printing, with varying interpretations of the genetic compass.

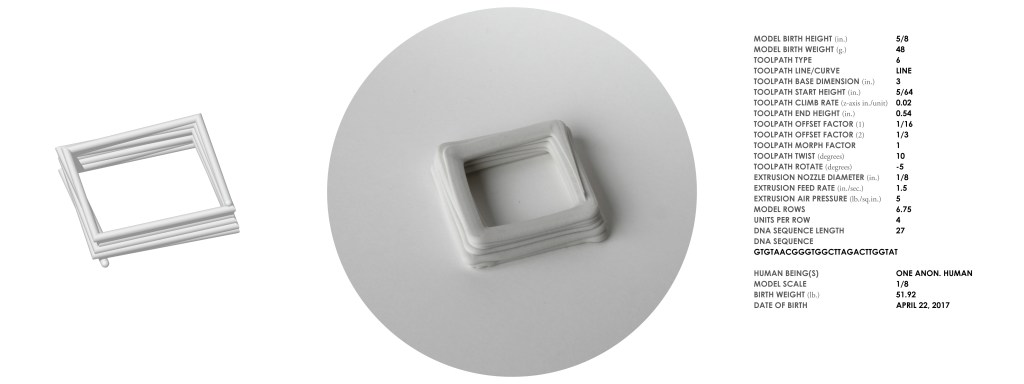

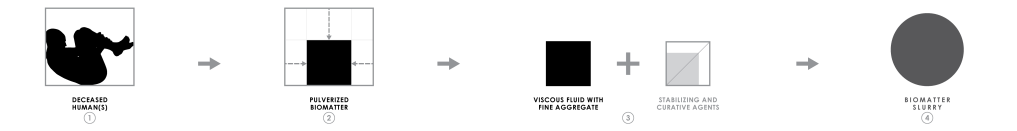

These 1:8 scale models simulate a process that reformulates the pulverized and slurried biomatter of a deceased human (or humans) with a formal translation of their genetic information to create unique proto-architectural design artifacts — artifacts of human being.

- (1) Supplementing the conventions of decomposition and disintegration, this introduces the paired processes of pulverization and concretization,

- (2) compacting and milling the entire quantity of one or more deceased humans’ remaining biomatter into a viscous combination of fluid and fine aggregate.

- (3) This substance is then blended with minimal amounts of cement-like stabilizing and curative agents, in a quantity up to equal the mass of the input substance. This quantity varies between each input, based on the relative lipid content of the given substance.

- (4) The resulting material is an actively curing slurry mix.

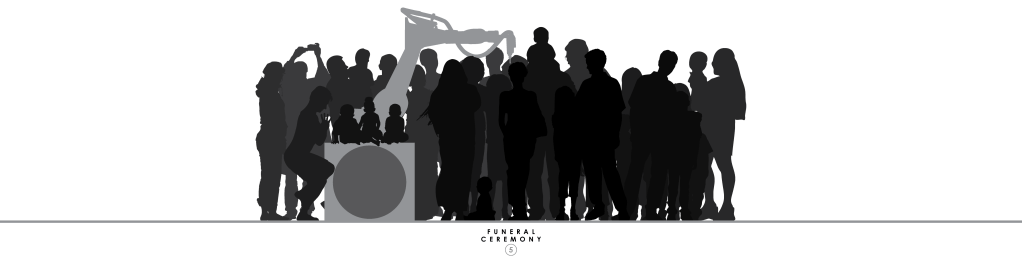

- (5) This slurry is input into a mobile robotic extrusion device, and deployed at the predetermined resting site of the artifact. The material extrusion process becomes a performative funeral ceremony, a new ritual gathering.

The series of speculative models produced for this project uses water-based acrylic latex caulk as a material approximation hypothetically comparable in both viscosity and chemical composition to the aforementioned corporeal slurry.

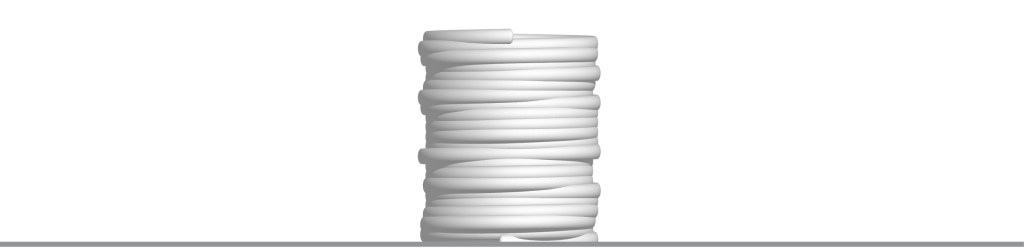

The viscous slurry is extruded pneumatically, harnessing air pressure to mechanically breathe the material from the orifice of a robotic appendage. Through the assistance of CNC (computer numerical control) automation, the extrusion aperture moves through space in a gestural choreography, leaving a trail of printed material — of sculptural ink.

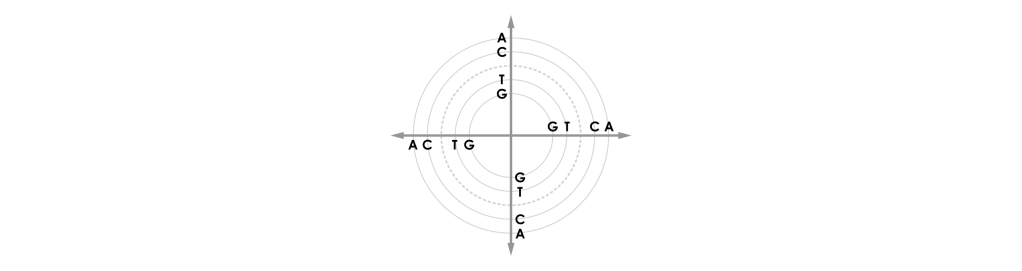

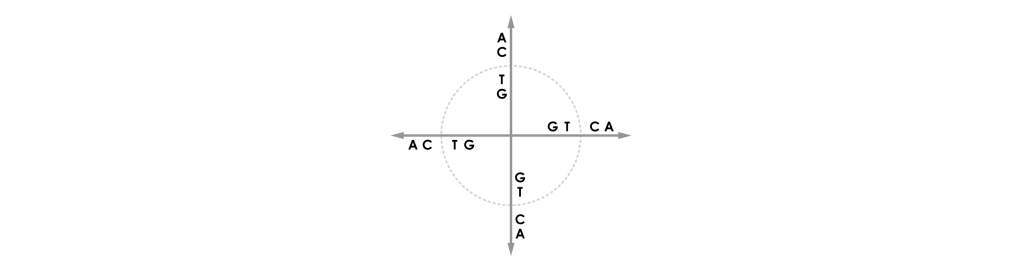

As the extrusion rig prints the matter into space without the support of formwork, a select sequence of its genetic information informs the rhythmic formal variations in its curvilinear toolpath. From a (0,0) point, the robotic appendage reaches out to the four compass points as it slowly climbs the Z-dimension on an axis extending from the center of the earth, through the center of the artifact, and into space.

Through this esoteric geometric choreography, the artifact is born as a concretized embodiment of human matter, of human information, of human being.

The genetic compass serves as the basis for the development of a morphological series of formal translations for the ritual artifacts of various sects over time.

This produces a wide variation of extrusion toolpaths across a spectrum from cross to circle, from interiorized, four-limbed, “bodily” entity, to hollow, “bodiless” entity.

These parametric translations inevitably result in unique formal configurations, even from identical streams of genetic information. In this case each unique translation toolpath embodies the same one hundred consecutive bases of DNA.

As all human beings share a vast majority of their genetic sequence in common, all of the artifacts excerpt from the same stream of information, a basic protein building block that occurs in the DNA of all humans. Difference between the artifacts is therefore registered through the act of design, in the variable parameters of their formal translations.

This difference is embraced in ritual congregation.

Embedded in each human being artifact is a unique set of design parameters that reformulate a unique quantity of matter — subject to unique externalities — into a unique and irreplaceable formal configuration. Reflecting the intentions of their respective makers, variations in these parameters have drastic influence on the final character of these artifacts.

Each artifact is a product of its designer(s)’ personal choices:

The choice for a bodily, limbed form, or an increasingly bodiless and open one.

The choice between smooth, controlled material extrusion, or more seemingly random and wild coiling.

The choice between striving for height, and possibly overreaching, or accepting one’s material limitations and increasing in base width.

The choice between formally emphasizing its embedded information and reducing its structural viability, or maximizing the quantity of information embedded by reducing its formal legibility.

Although these esoteric parameters might not be directly discernible, their effects are nonetheless exhibited in the artifact, and reflect the broader cultural and ritual aspirations of the designer.

As artifacts of architectural design, these objects beg for human interaction:

A human bends over and curiously sniffs one, smelling it like a flower.

A human sticks out their tongue and tastes one, curious to see if it might be familiar to their palate.

A human touches and feels and gropes one, feeling its luscious curves and slumps and folds and coils.

A human cradles themselves inside of one, hearing sound echo in a ghostly form of communication.

In Architecture of First Societies, Mark Jarzombek describes the megalithic artifacts of Carnac, France as an accumulation of arduously quarried, transported, and placed stones that represent a long series of successive generations. (380) In rows unevenly space and unevenly aligned, each grand stone artifact memorializes an individual human or generation of humans, and through their aggregation, the artifacts express a greater lineage, a past human culture.

- Mark Jarzombek, Architecture of First Societies: A Global Perspective (Hoboken: Wiley, 2013).

- Photo credit: Clemens Koppensteiner, “Stones in the Fog 1” (2005).

In this new Carnac, this ‘post-mordial’ cemetery of transmogrification and transubstantiation, these artifacts truly strive to become embodiments of human being, existing as totems of past human lineage, and ‘memento mori’ for those remaining. The artifacts blur the boundary between organism and environ, human and non-human, living and nonliving, subject and object.

Human Being Architecture.

VIEW THE PROJECT DOCUMENTATION IN FULL

- Digital media: Rhino, Grasshopper, Mastercam, AutoCAD, Ai, Ps

- Physical media: water-based latex caulk extrusion-printed via pneumatic power on CNC ShopBot

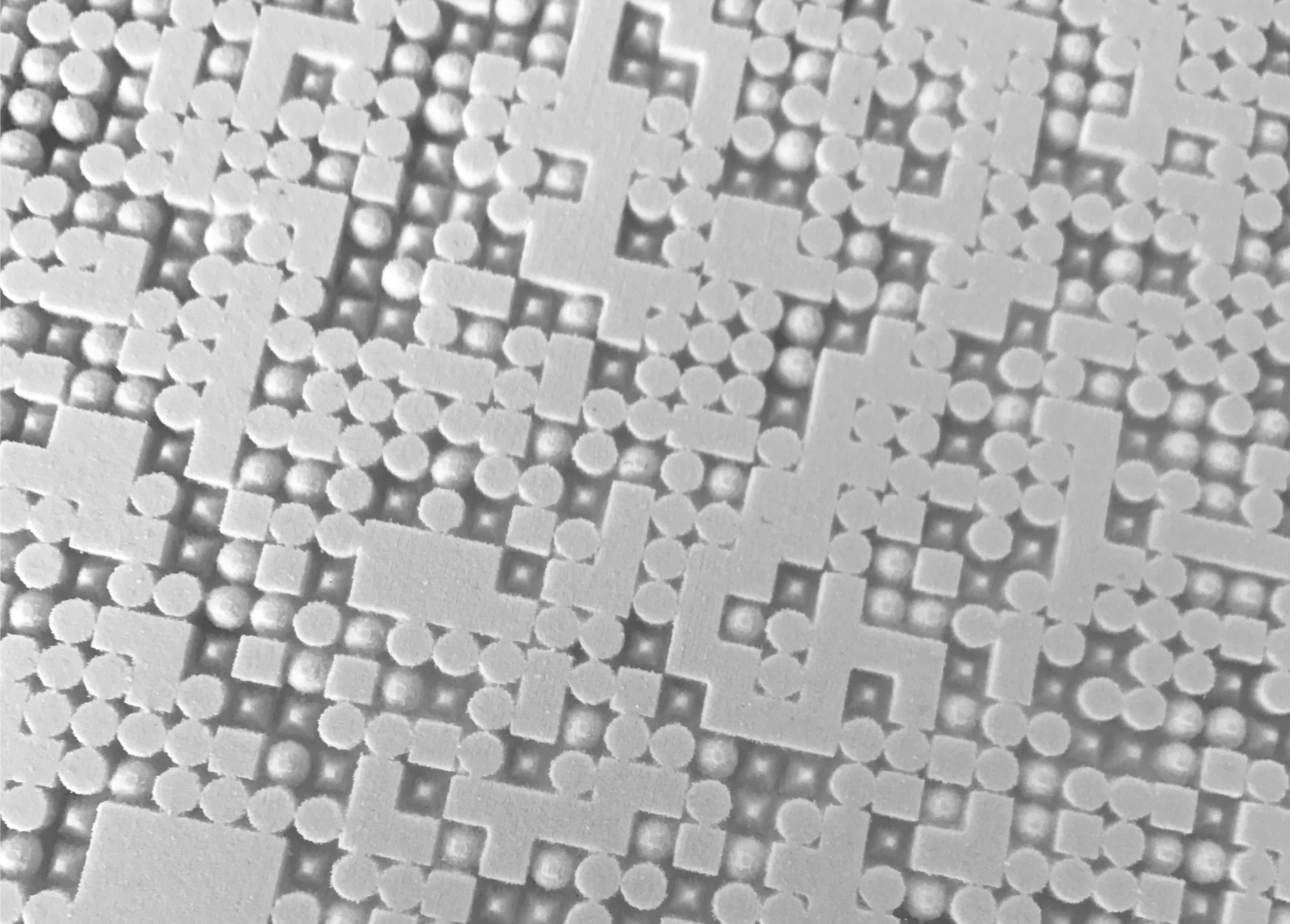

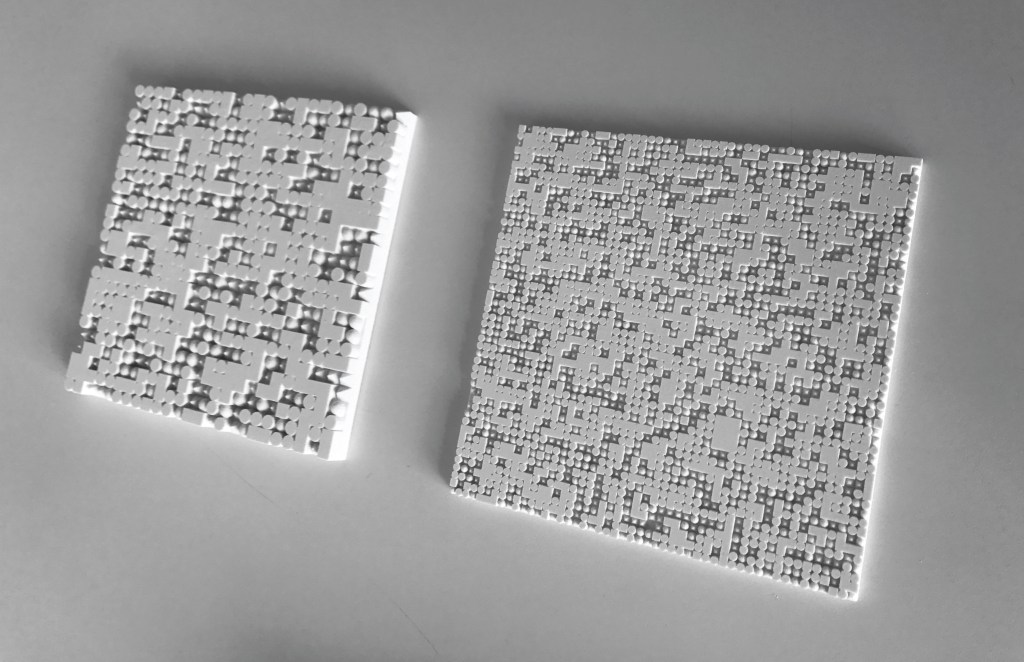

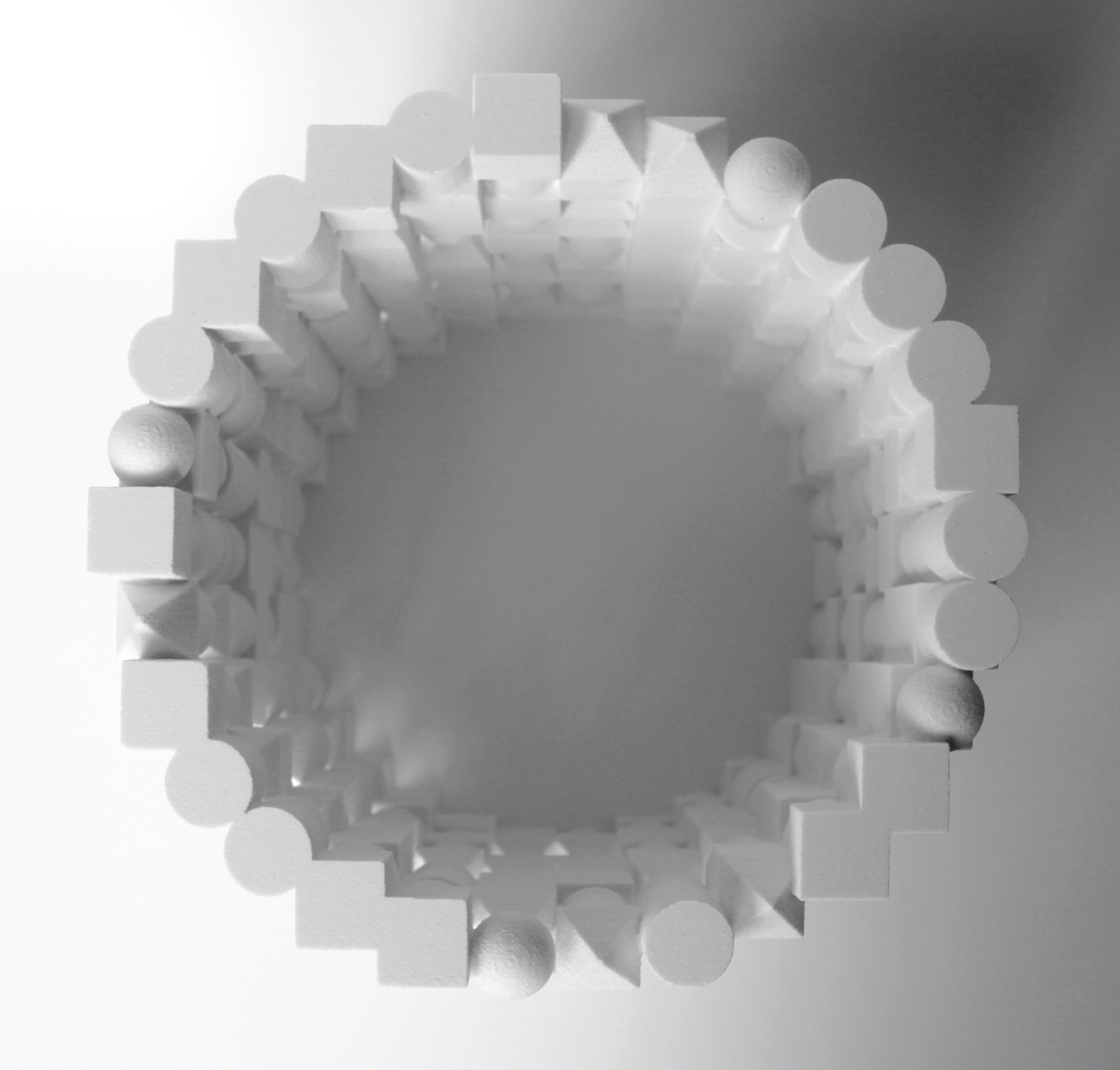

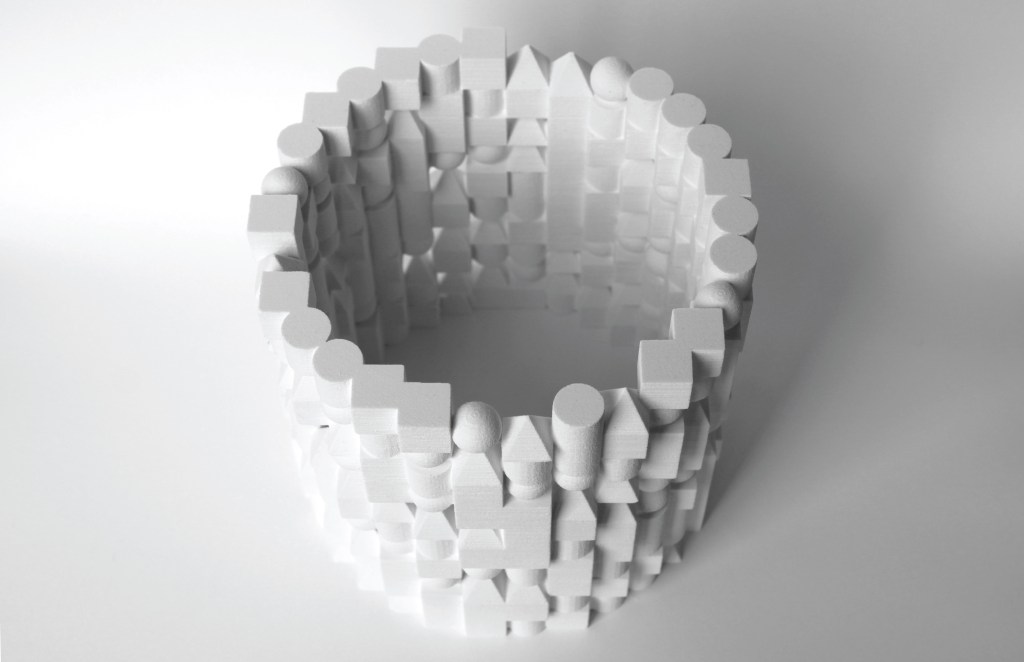

ARTIFACT EXPERIMENTATION

“Point-to-Shape-Solid” Plane:

“Point-to-Shape-Solid” Cylinder:

“Point-to-Shape-Solid” Plinth:

“Point-to-Shape-Solid” Ring:

“Point-to-Surface” Surface:

“Point-to-Line” Volume:

VIEW THE PROJECT DOCUMENTATION IN FULL

PROJECTS: ABODE // CABIN // SEMI-SUB-URBAN // STATION // GREEN // TRANSPOSITORY // TEA-CRETE // LIGHTS // PENDANT // RINGS // NEO-CAIRNS // THESES: METAMATERIALISM (Human Being) // POST-MORDIAL (MIT SMArchS) // ISOTOPIA (Syracuse BArch) // HUMANS: KRIS // JODY

© Human Being Design 2025